On the river behind St. Albert Place, at the Healing Gardens, red dresses wafted on the Friday breeze, their fabric billowing then going slack as if haunted by memories of the missing and slain.

It was Red Dress Day—a reminder of the nation’s missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

It’s the second year of co-organizing the display for St. Albert’s Cheryl Lundy-Stuart.

“It’s very powerful to see them flow in the wind, they seem to come alive,” she said. “It’s really quite overwhelming.”

The dresses tell stories, with attached photos and remembrances.

“Each dress tells the story of one of the many women who never had a chance to live,” she said.

Last year, a similar display at the site stayed up from May 5 to the July 1 Run for Reconciliation.

A book in a plastic container invites site visitors to record their thoughts on seeing the moving display.

Display co-organizer and St. Albert resident Amanda Patrick was raised with some Indigenous culture in her Métis family.

“I spent the last few years trying to find my place as a Métis woman,” Patrick said.

The red dress display came from that impulse, she said.

Patrick has had a family member living a high-risk lifestyle, who went missing but then was found safely. She’s shocked by the statistics.

“Once you start reading, the facts are crazy,” Patrick said.

“In 2022, there were over 600 missing alerts—two-thirds of the missing alerts were for Indigenous people,” she said.

About 84 per cent of cases in Alberta are murder cases, according to the Native Women's Association of Canada (NWAC). That number is considerably higher than the national average of 67 per cent.

About 70 per cent of the Alberta cases involve women between the ages of 18 and 44.

Too often cases of missing Aboriginal women are stereotyped and/or dismissed as involving only ‘run-aways,’ the NWAC release said.

“Not only is this untrue, it implies that young girls that do ‘run-away’ are somehow undeserving of attention or protection,” it said.

The vast majority of cases of known individuals in Alberta (almost 90 per cent) involve mothers.

Some 76 per cent of Alberta’s missing women and girls disappeared from an urban area, which is higher than the national average.

“In Alberta, only 42 per cent of murder cases in NWAC’s database have been cleared by charges of homicide. This is far lower than the national average of 53 per cent,” the release said.

However the percent of cases cleared by suicide is among the highest in Canada—almost three times higher than the national average.

Overall, the percentage of unsolved cases in Alberta is still comparable to the national average— 42 per cent in Alberta.

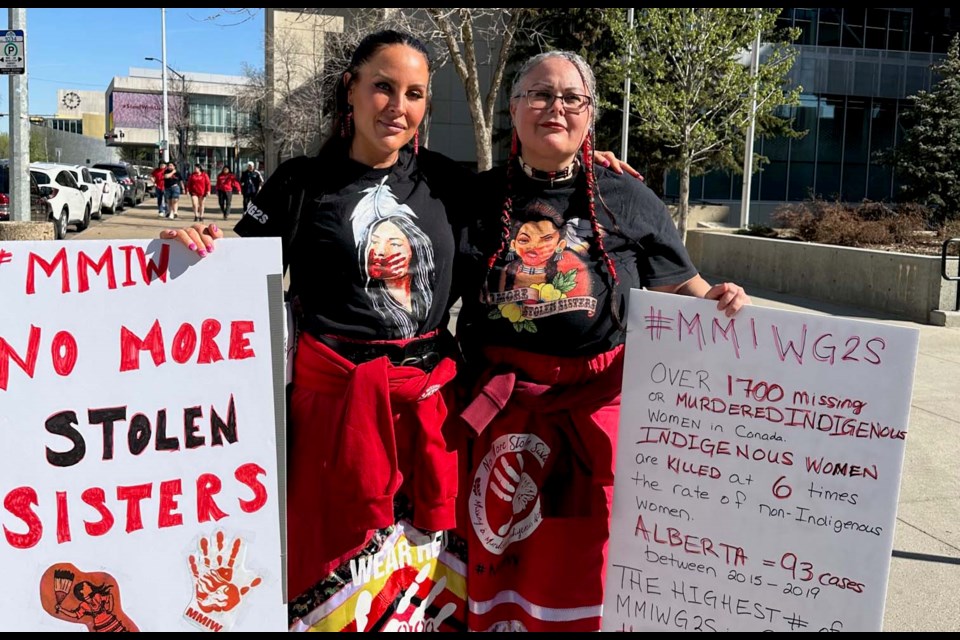

Indigenous women in beautifully adorned traditional red skirts on Friday morning at City Hall in Edmonton for National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and Two-Spirit people.

A long name to address longstanding injustices, the day brought Rhonda Wood-Viscarra out to bring attention to entrenched and shameful truths. A member of the St.Albert-Sturgeon County Metis Local #1904, she cited numbers from the NWAC that show provincial statistics here are worse even than the still-shocking Canadian averages for Aboriginal women and girls in Alberta who go missing or are murdered.

“There are 93 cases of missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls in Alberta. This accounts for 16 per cent of all cases in NWAC’s database,” a NWAC release said.

The number of cases in Alberta is second only to British Columbia (which accounts for about 28 per cent of all cases)

“Ninety-three cases in Alberta, that’s unacceptable,” Wood-Viscarra said, the morning sun glinting off her traditionally beaded earrings in the shape of red dresses.

“As Indigenous women, we have to stand up for our sisters who have gone missing,”

Indigenous women who go missing are just as important as non-Indigenous, she said.

“It’s important for Alberta to take a stand, and not just talk. We need action,” Wood-Viscarra said.

Alanna Tyler, also of the Metis Local #1904 for St. Albert/Sturgeon County, said attention must be paid.

“There’s not enough recognition in Alberta and Canada when our indigenous people go missing. You don’t get the same response,” Tyler said. “We need to see follow-ups, we need to see action. That’s what today is all about.”