Scientific St. Albert

The Gazette is using science to answer questions from students of all ages about the world around them. Send in your questions to [email protected].

Science is everywhere in St. Albert, from the air we breathe to the Earth we walk upon, so it’s no surprise folks might have questions about how it makes the world work.

Eight years ago, I ran a column about the science of everyday life called Scientific St. Albert. I stopped because I ran out of questions to ask.

But it turns out kids are full of questions! For the next few months, I will be answering science questions St. Albert youths have about the world around them.

This week’s question comes from Allison McCrea of Four Winds Public School in Morinville, who asks, “If air was a colour, would it be orange?”

The answer depends, in part, on how we define “air.”

The whole sky

First, let’s define it as “atmosphere,” or “the sky.”

Air is normally transparent and colourless, says University of Alberta physicist John Davis. If it had colour, that would mean it somehow absorbed or cancelled out some part of the visible light spectrum; grass is green because it absorbs blue and yellow light. If humans could see infrared light, air would have a colour, as the carbon dioxide (CO2) in it absorbs infrared, causing global warming.

So why does air look blue, orange, and other colours when it’s in the sky? That’s because of Rayleigh scattering, which is the scattering of light waves caused by molecules in air. Blue light has a shorter wavelength than orange and red, so it takes less air for it to scatter so we can see it.

If you look near the sun at noon, the sky looks white as not much light scatters and we see all the wavelengths at once, Davis says. Look farther away, and there’s enough air to scatter light a bit, so we can distinguish the blue wavelengths. At sunset, there’s so much air between us and the sun that the blue light is scattered to the point we can’t perceive it anymore, leaving only the less-scattered reds and oranges.

What if we change planets?

On Mars, the atmosphere is mostly CO2, and the sunsets there are blue, notes Frank Florian, senior manager of space science at the Telus World of Science Edmonton. By day, the sky looks red due to all the dust in it.

Air on Venus is dense with lots of CO2 and sulphuric acid, and would probably look dark beige because of all the light scattering, Florian said. The atmosphere on Titan, a moon of Saturn, looks orange because it’s mostly methane.

“If you could go down in the clouds of Jupiter, you’d probably see that wherever you were the sky would be a different colour,” Florian said, as it’s made of a whole bunch of different gases.

Just a jar

But what if we use a smaller amount of air — say, a jar’s worth?

Air is about 78 per cent nitrogen, 21 per cent oxygen, 0.9 per cent argon and 0.1 per cent other stuff, says MacEwan University chemistry professor Lucio Gelmini. Under certain extreme temperatures and pressures, these gases can have colours.

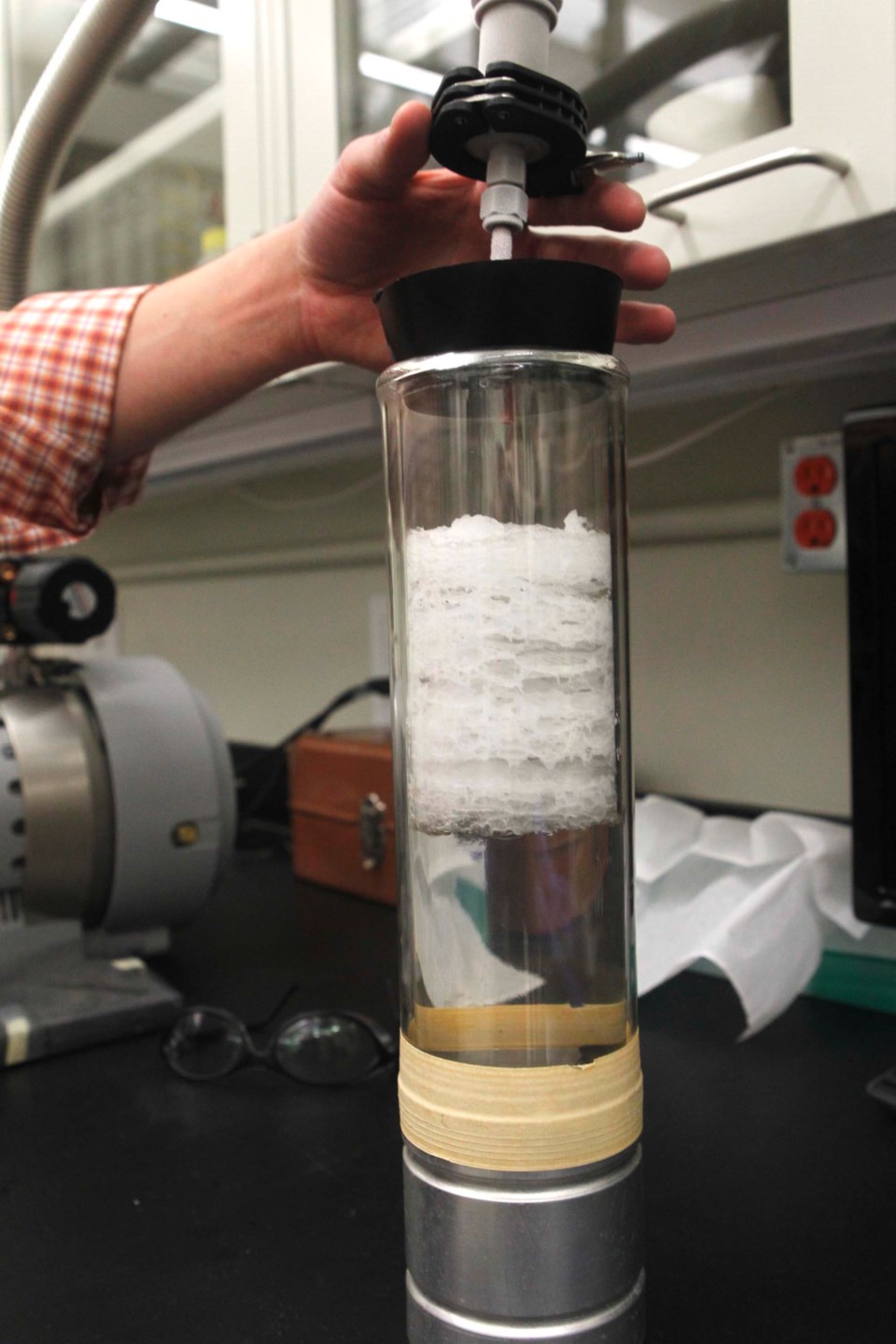

The nitrogen part of air is colourless, Davis said. It looks white when it’s solid at about -210 C because, like a cloud, it has a whole bunch of different particle sizes which scatter all wavelengths of light, resulting in white.

Argon is colourless at all temperatures, but if you zap it with electricity it looks pale red or steely blue, depending on the pressure, reports the Encyclopedia Britannica.

If we take our jar of air and cool it to at least -183 C, the oxygen in it turns into a blue liquid, making our air pale blue, Gelmini said. The oxygen stays blue if we freeze it solid at -218.4 C.

If we crush that solid oxygen with about 10 gigapascals of pressure (about 99,010 times what we experience on average in Edmonton), weird stuff happens. As reported by Yu A. Freiman, the massive force alters the oxygen’s molecular structure, changing it from a light-blue crystal to an orange and then red one.

Air doesn’t normally have colour, but on the right planet at the right time, or at the right temperature and pressure, it can be orange.