Like most mothers, Roma Kurtz wants her children to attend a post-secondary education facility.

Her sons, Ben, 22 and Grant, 20 have severe autism. They are non-verbal and have developmental disabilities, but both men graduated from high school. Ben graduated two years ago from Paul Kane and Grant graduated from Bellerose last spring.

Roma applied on their behalf to several local schools: the University of Alberta, NAIT, King's College and Grant MacEwan University, but all applications have been refused.

"There are very few programs for them, but I would like my boys to do post-secondary education. There are very few places for people with special needs. I applied but others were chosen, but not my boys," Kurtz said.

Sit with Kurtz and her boys and their aides for a few hours, and you will be transported to a different world.

The Kurtz home has been made safe, or at least as safe as possible. The doors have high latches, to prevent the men from running outside. The floor is wooden to minimize falls or tripping. The furniture is placed to accommodate sudden lunges or spastic-like jerky limbs that may unexpectedly make a dive for a chair or a couch. Both men have individual assisting aides, who stay with them throughout the day until 9 p.m.

Both appear to be creative and artistic, yet when their art is proudly displayed by their mother, the men are unresponsive. Still, there are tiny hints that there is understanding. When Grant wants to go upstairs, he grabs a card that says, 'upstairs' and his aide allows him to go. Similarly, when he wants to eat or is hungry, Grant will point to the 'food' card.

A person with little experience with autism or developmental difficulties might ask, "How can these men go to post-secondary schools?"

Kurtz asks, "How can they not?"

"When my boys went to kindergarten, there was someone to hold my hand. All through school they were included and they did things with the rest of the school. Now there is a piece missing," she said.

Band and Outdoor Ed

Grant, who is the most recent family graduate, was very much part of the Bellerose High School community, said principal George Mentz.

"Grant was full-on into the schedule. He attended classes with a personal assistant. He had as much inclusion as everyone deemed appropriate for him," Mentz said.

Some classes were specially geared for him, but he did learn elementary math skills and enjoyed being read to.

"He especially enjoyed music and art and outdoor education. You get that kid outside and you could see his joy and his enthusiasm. In band he played light percussion instruments and he attended outdoor education camps and band camps," Mentz said, stressing that if Grant became agitated or over-excited, his assisting aide simply removed him for a few minutes until he settled down.

"I cannot remember a time in either Grade 11 or Grade 12 when there was an incident, but if he had been disruptive, he would be removed from class, just as any disruptive student would be removed from class," Mentz said.

Now, with no school, the days are empty for Ben and Grant but Kurtz has tried many different ways to keep them engaged with society and active, including taking part in various volunteer commitments.

Photography and painting

Kurtz made what she calls an interest wheel, and listed every possible activity or thing that she had noticed sparked some interest in her boys.

"I asked what would be the next step if they were other 20-year-olds. If they were other 20-year-olds they would pursue their interests. They would hang out with friends at school, " she said.

Ben often stares intently at things and he likes to click buttons. Kurtz asked Brock Kryton, a student at Grant MacEwan University and a professional photographer, if he would work with Ben.

Once a week Kryton takes Ben on a photo shoot, which often involves walking from place to place.

"I'm his mentor, but really, Ben is my mentor. I've learned to see the world differently through Ben," Kryton said.

Kryton tries to understand what fascinates Ben and then lines the viewfinder of the camera in such a way as to frame the "thing." He pus Ben's finger on the camera button, so he can shoot the photo.

Together they produced some unusual shots, including a series of black and white studies of an acrobat, who performed at the St. Albert Children's Theatre.

Kryton has found the experience of shooting photos with Ben to be emotional and it has made him question his own beliefs about schooling. He has tried to stimulate interest among fellow photography students at Grant MacEwan, to join a photography club with other people with autism.

"I've learned I had to reserve judgment on all the stigmatisms that I had. We assume there are things he cannot do, but often he can do those things," Kryton said.

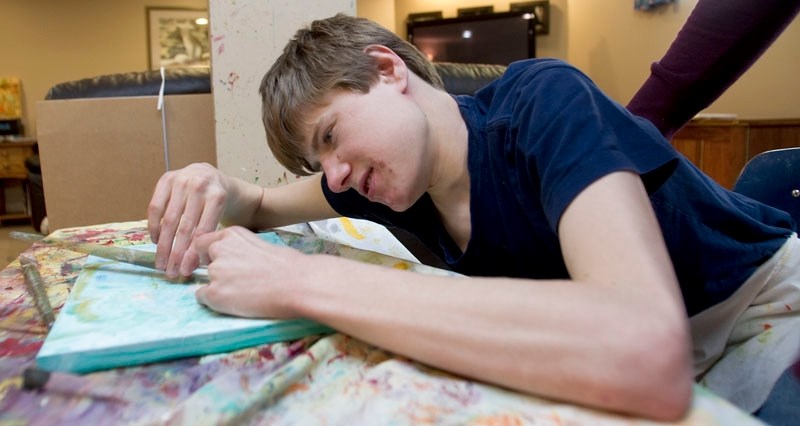

One of Grant's interests is painting. His mother asked artist Diane Cardell to work with her son and together they produced colourful pictures full of bright sprays of paint.

"When they paint together, it's like the choreography of two, on canvas," said Kurtz.

Deborah Barrett, whose son Anthony is presently attending NorQuest College understands the difficulties for parents wishing to enrol their special-needs children in post-secondary education.

"My son is 23 and he is now a student at NorQuest College, but when I first tried to enrol him in post-secondary schooling there were only five positions available for people with disabilities in all of Edmonton. And there were 40 people waiting for those positions," said Barrett, director of community awareness at the Autism Society of Edmonton.

Anthony, who is autistic and non-verbal, is attending adult literacy classes. Most of his classmates are taking the classes because they are new Canadians and English is not their first language.

"They come from somewhere else, but when you think about it, Anthony comes from someplace else, too," Barrett said.

Anthony is not registered in a separate curriculum and he is getting high marks, even though he cannot speak. His mother argues that Anthony is not disruptive because he is busy and learning skills. She hopes one day he can use those skills, along with his demand for orderly progression, to work in such places as a hospital, where he could deliver mail or do other routine tasks.

"He is getting 80 and 90 per cent and when he got 100 per cent, his classmates stood up and cheered for him," she said.

Together Kurtz and Barrett have become advocates for those adults with learning disabilities or developmental delays.

Kurtz has organized an art show Oct. 5 between noon and 7:30 p.m. at The Citadel Village (St. Albert Trail and Erin Ridge Road).

It will be an opportunity to meet Ben and Grant and to see their art. There will be a special presentation and silent auction to support the Autism Society of Edmonton.

"When you meet people with developmental disabilities you learn something about the value of being human, beyond the economic level," said Barrett as she also argued that the economics of keeping young people shut up in their basements with an aide as caregiver, doesn't make sense. Barrett believes that jobs would be created if schoolroom facilities were provided to people with disabilities.

"If we could have classrooms, with one or two teachers, then you would create jobs. The two parents could keep their jobs. The teachers would have jobs and the persons with developmental disabilities could learn how to make a contribution to society," Barrett said.

Though he cannot speak, Grant Kurtz would likely agree. With nothing to do most days, he appears agitated, perhaps because he is bored or perhaps because he is frustrated at his inability to communicate. Mentz never saw him disruptive in class, but now he is constantly on the move and often tries to run out the front door. His frustration grew once September came and he seemed to sense that he was not going to school.

"The bus stopped coming. Grant loved to go on the bus. He ran to the bus. He had a purpose and a reason to get up each morning," Roma Kurtz explained. "He misses school."