Renewable energy projects have been a boon to municipal tax revenue in southern Alberta.

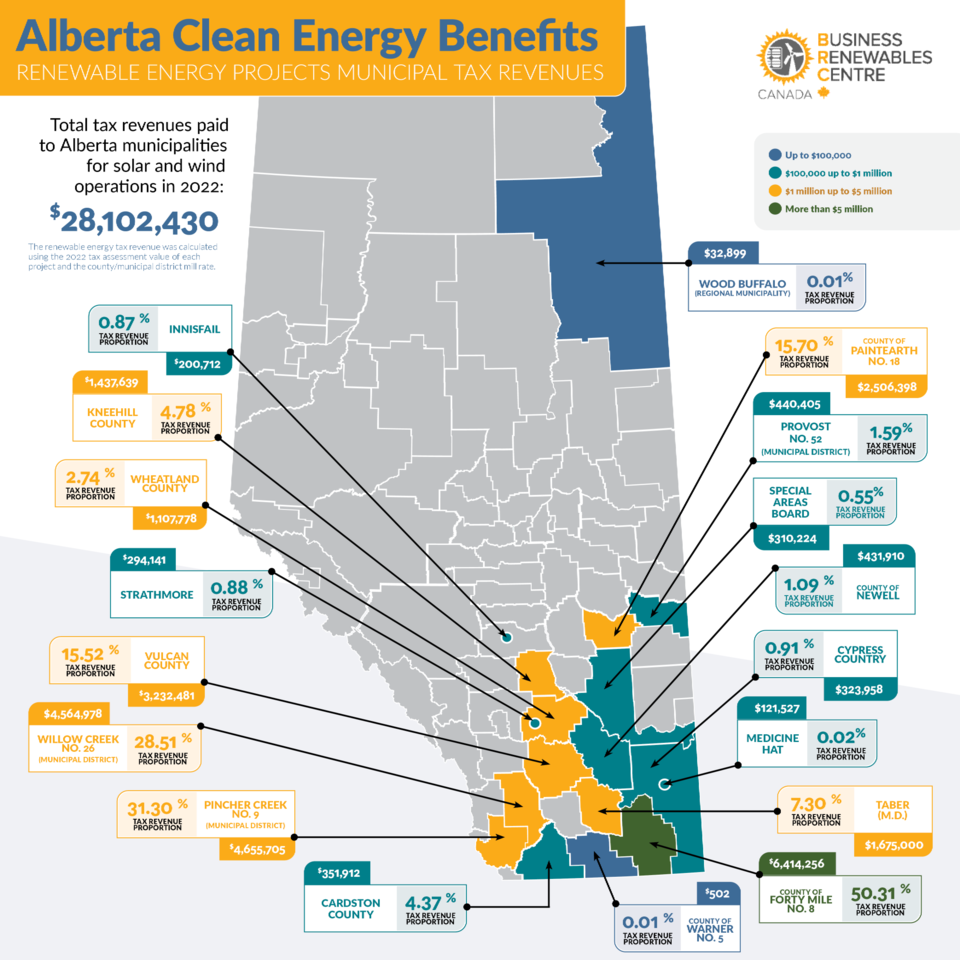

In 2022, wind and solar operations brought in over $28 million in tax revenue to Alberta municipalities, almost three times the amount estimated in 2017, according to an analysis from the Business Renewables Centre-Canada (BRC-Canada), a Pembina Institute initiative.

Using the tax assessment value of each project and local mill rates, the group calculated how much was paid to municipalities. The proportion of tax revenues coming from renewables ranges from 0.01 per cent in Wood Buffalo to 50 per cent in the County of Forty Mile No. 8, with most high earners found in southern parts of the province.

“Eight of the 18 districts with renewable energy projects are already seeing over $1 million of revenue,” said Jorden Dye, director of BRC-Canada.

“And because this is the 2022 assessment, there are lots of projects that have already finished construction but weren't operating for a full year for them to be included in the property assessments,” he said.

The Travers solar farm, the largest solar project in Canada, hadn’t been operating long enough to be included in the assessment, said Dye. Even without including the Travers project, Vulcan County drew 15 per cent of its tax revenue from renewables in 2022, according to the analysis.

“As we look forward, and more counties drive past that million-dollar mark, we're talking about a significant value for these municipalities,” Dye said.

“It's a good thing for the county as a whole, because our main taxes came from oil and gas, and that has dropped significantly. So, it's nice to see the renewables pick that up,” said Craig Widmer, reeve of County of Forty Mile No. 8.

The county collected more than $6 million in tax revenue from renewable operations in 2022, according to the analysis. Widmer said most comes from wind turbines, but there are a couple big solar projects on hold right now, “that could surpass the wind.”

Perspectives on the growth of renewable energy projects vary in every part of the county, with some accepting it as an inevitable change and others wanting to limit the amount and location of development, Widmer said.

“Our perspective is, it's basically taxes for us, and the amount of service we can give to our residents. I mean, if the money isn't there, we have to cut services, and we don't want to go backwards.”

Innisfail Mayor Jean Barclay said the town was the first urban area in Alberta have a solar project on municipal owned land. Since construction of the hundred-acre solar farm, which is privately owned and operated, community opinion on the place for renewable projects in their town has shifted, she said.

“Let's face it, we are an oil and gas province, and it was something new,” Barclay said.

“But over time, I think our community has really evolved. We've been very diligent in looking at opportunities for revenue generation. You know, our toolbox is so narrow with where we can find new revenues outside of raising taxes, raising franchise fees, raising utility rates, that we're certainly spending lots of time considering what can be done and how we can improve our top line revenues.

“And certainly, solar arrays and solar projects are one of those things,” she said.

Innisfail is considering another solar project in an industrial park currently under construction, which would be owned and operated by the town, Barclay said. The 1.5-to-2-megawatt project would generate an estimated $500,000 in revenue per year. However, its progress has been delayed by the provincial renewable energy moratorium.

In August, Alberta’s United Conservative government paused approval of all new renewable energy projects until February. Dye said the move will create an eight-month backlog of projects and any regulatory changes coming out of the moratorium could have major impacts on municipalities.

“I think the biggest concern right now is that if the cost of these projects is raised significantly, then we're going to see a lot of the projects that are currently in the queue drop off. And when we look at the connection queue going forward, our current estimate of the revenue that will flow to municipalities from projects that are in the queue to date is between $170 and $250 million. So, we're talking a significant amount of municipal revenue,” Dye said.

The towns of Innisfail and Caroline both sent letters of concern over the pause to the Alberta government.

"This moratorium is harmful to municipalities like ours, preventing us from generating needed revenue to keep property tax increases at a minimum, while continuing to provide the services and facilities required to retain and attract new residents and businesses," a letter signed by Barclay said.

Although the County of Forty Mile No. 8 has also been affected by the pause, Widmer said he supports the moratorium because municipalities need to have more say in how things are done and where projects are built.

“We’ve just got to be careful. I’m not opposed to renewables in our county, it’s just how they’re being done,” he said.

Widmer said most companies looking to build wind or solar projects in the county have been willing to work with the local administration, “but the odd one would bypass us.”

“They would come and talk to us, and if they didn't like the restrictions we put on them, they just went higher up to the (Alberta Utilities Commission), and the AUC makes the final decision,” he said.

Municipalities should have a clear place in the decision-making process, he said, and there need to be guarantees that the companies have money set aside for reclamation when the project ends.