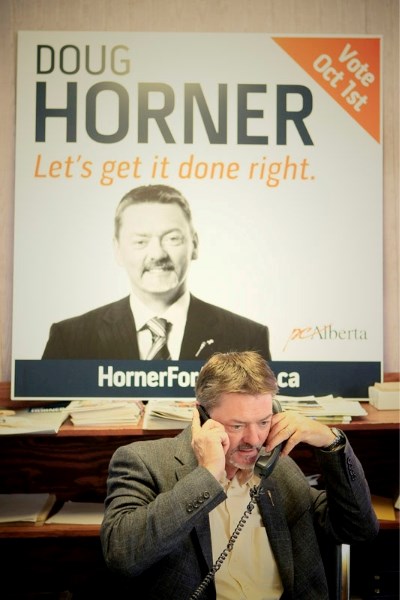

In his cluttered campaign office, working two phones at once, Doug Horner has a big wide grin. His marathon race for the Progressive Conservative leadership is over. He's travelled the province, spoken at two and to three functions a day for months, given countless interviews and shaken god knows how many hands.

Unfortunately for him, Horner's grin won't last the evening,. Soon the numbers will be clear, but at this point the phones are telling him what he wants to hear.

"There is a good feeling out there. There is good energy out there."

It is 3 p.m., four hours before the polls close and seven before his crushing defeat will become inescapable. Horner is hearing what he wants — turnout is up, especially at rural polls.

The phones in his office have been ringing all morning, taking over 200 calls. The calls are from people looking to help, looking for their polling spot and, even on voting day, looking to know more about Horner. The office, which served Rona Ambrose during the federal election campaign has a tattered temporary feel to it. It's purple-hued walls scream paint sale, the carpet is worn and industrial and the furniture, like in most campaign offices, has a sterile quality to it.

But on top of the furniture are phones and in addition to all the calls coming in, volunteers are calling out to make sure Horner's supporters vote.

In the afternoon, Carol Stewart, an organizer who normally runs Horner's constituency office, asks who to call now because they have called everyone once.

Horner's answer comes quickly; start at the beginning and start calling again.

He is not nervous yet, but he will be.

"I will get nervous, there is no question about it. It will happen sometime later today," he said. "I will start to get nervous about 9 p.m. tonight."

His team isn't nervous either — a calculated strategy has them thinking this campaign is winnable, that they are poised for a surprising victory.

Starting out

Horner's quest to become premier began days after Premier Ed Stelmach stunned the province with his snap resignation.

The deputy premier, Horner only learned Stelmach was going to quit hours before the announcement.

There was simmering concern at the time in Calgary about the budget and the government's direction and Horner was on his way there to smooth things out.

"I was going to have some discussions as the deputy with some of the folks, because my job as the deputy was to watch the boss' back."

Horner was taken aback.

"It was a shock. It was one of those moments that takes your breath away."

In an instant, Horner no longer had to worry about his boss' back, he now had to think about his opportunity.

He began consulting family and friends, slowly widening the circle, until he had an idea if this was a move for him.

The team

Kevin Weidlich, definitely thought it was.

Weidlich, who became the operations manager of Horner's campaign, sent a text message to Horner the day after Stelmach's announcement.

"If you are thinking about doing what I think you should be doing, give me a call," it read.

Weidlich got the call a week later when Horner invited him over. He told his family and friends he would seek the leadership.

Then unemployed, having left a job in December, Weidlich had taken some down time, but was prepared to start looking for work when Horner asked him to come on board.

Horner's all-volunteer campaign offered no salary, but a combination of severance and part-time pay from the army reserves was enough to get by.

"My wife and I sat down and we figured out the math and we said OK, it's not going to be easy, but we can do this."

Weidlich doesn't see the contradiction in passing on paid work to work for free.

"I come from a military service background so I have a sense of public service and without sounding all too schmaltzy, I think it is the right thing."

The military is Weidlich's connection to Horner. They served together as reservists and like many volunteers, the personal connection is his motivation.

Stewart has worked in Horner's office for 11 years and each year she banked some vacation time for a once- in- a- lifetime vacation. When Horner made his announcement, she found another use for that time.

"I took my holiday time and went for it," she said. "I will get it in another lifetime."

Horner's media liaison, Jeanna Friedley, worked for him in his cabinet office. She came to the campaign eight months pregnant. Her maternity leave became campaign time and while juggling phone calls, she usually has her infant son — born two weeks before the first ballot — in the other hand.

"I needed to make time. It is important enough to me and the future of my family and I believe enough in Doug."

The 20 Horner-branded vehicles the campaign used are another sign of commitment. They are personal vehicles the volunteers paid to have decaled.

Horner said the support leaves him with a mixed set of emotions.

"Humbling and it scares the crap out of me," he said. "It certainly gives you a feeling of 'wow, I have to perform.'"

Strategy

When all the votes were counted, Horner was far behind his opponents, but in some ridings he not only won, he dominated. In Lac La Biche- St. Paul, home to Minister Ray Danyluk, he put up 1566 votes, good for 79 per cent, the most lopsided win in the province.

Other rural ridings followed the pattern. In Athabasca -Redwater he took 67 per cent and in Barrhead- Morinville- Westlock it was 71 per cent.

The campaign's central strategy was to make sure Horner's supporters voted. Getting the most votes to win an election is hardly rocket science, but Weidlich said the strategy meant identifying who would support Horner as he was and then making sure they cast voted.

On the office wall, the electoral map has small MLA pictures, coloured in orange if the riding supports Horner, with an added check mark if the MLA publicly endorsed him.

Tied into the strategy, Horner didn't seek all MLA's endorsements equally. He sought the MLAs with the most to offer.

"There are MLAs who can turn out the vote and there are MLA's who can't," explains Weidlich. "If you are an MLA who is well-connected with your constituency association, you are going to turn out your vote."

Weidlich said a party membership list and Horner's own knowledge identified those MLAs and he focused on them.

"We don't go hard after them. That isn't to say we didn't go after everybody, of course we did, but the guys we really want are the guys who are willing and able to work."

In the campaign office Saturday, it was those MLAs Horner was calling. Asking all of them the same questions about turnout and they all had good news. Even when Horner voted Saturday morning, traffic there was steady and in Weidlich's mind, promising.

Not all of the smiling orange-shaded ridings, what Weidlich called the "power ridings," had MLAs endorsing Horner. But in some, the MLA endorsement was less important.

St. Albert MLA Ken Allred, for example, endorsed Ted Morton and then Gary Mar, but the riding went to Horner in both the first and second ballot, first with 38 per cent of the support and then with 40 per cent.

Before the results came in, Horner said he never anticipated getting Allred's support.

"He didn't bring his riding for Ted. I didn't really expect him to come to me and I think today we are going to find he didn't really bring it for Mar."

Allred said he knew St. Albert would be a Horner riding, but he found the policies and principles that he supported and stood behind them.

Weidlich said the 20 power ridings received the brunt of the campaign's attention, especially in the closing weeks. They wanted respectable numbers in Edmonton and Calgary, but the power ridings were the key.

"A very deep pool instead of a broad shallow pool, relatively narrow, but very deep."

Stelmach 2.0

One of the electoral map's smiling orange faces was Premier Ed Stelmach's. The premier was neutral, but the riding was considered Horner territory.

Stelmach's primary influence on the campaign had little to do with his home riding. Weidlich said it was hard to shake the idea Horner was a Stelmach clone.

"It was frustrating to run against because personally I don't believe it. I have never met Ed Stelmach. I am Doug's campaign operations manager.You would think that if Doug was Ed Stelmach two he would have Ed Stelmach's organization."

Horner said it was part of a broader misperception that he was a rural northern candidate.

"Premier Klein put me in cabinet," he said. "I haven't lived on the farm for 32 years."

Counter message

In addition to shedding that image, the campaign used specific messages about Horner, again targeted specifically at his supporters.

If you saw Horner speak, read an article, saw the debate or were within a hundred feet of him, the campaign wanted you to know he was a team player, with international business experience who stood by his commitments.

"You can't be a leader unless you are a team player;, that resonates with Doug's supporters, so deliver that message and make sure Doug's supporters hear that all the time," explains Weidlich.

Friedley said it is about letting him tell his story.

"We don't have to message him — he just is him."

Weidlich said the business message was important, which is why Horner so often mentioned his experience making a payroll.

"People identify with someone who has been in business. Not only that, remember small business is 80 per cent of the economy, so we know there is a broad base."

Calgary cut off

Horner's message hit its biggest wall in Calgary. On the Sept. 17 ballot, Horner netted miniscule tallies, four votes in one riding, two in another and even a riding with a solitary vote.

"The fear of god was put into a lot of people supporting Doug, including me. We came within a hair of not even making the top three," said Weidlich.

Horner said he considered whether he should even stay on.

"When the pack narrowed down and those three other candidates went to other camps, the first thing was a gut check — do we stay in?"

The pressure to leave the race was also coming from the outside. While Horner left it at "another camp," Weidlich was more direct, explaining the Mar team wanted Horner out.

Weidlich said the calls came from Mar's MLA backers.

"I would say that was some of the most strain I have ever seen Doug go under."

Horner turned to a party elder for advice.

"I phoned Peter Lougheed and I asked him do you think I should bow out of the race for the good of the party?" Horner said Lougheed's answer was direct . "He said absolutely not; for the good of the party you stay in the race and for the good of the party I think you can win it."

To win, they would need to do a lot better in Calgary; a respectable showing to allow the power ridings to lead them to victory.

Weidlich said Calgary had eager volunteers, but no direction. When the defeated candidates endorsed Mar their supporters and organizers didn't follow. Former MP Eric Lowther had supported Morton, but came to Horner. He said the challenge of the final two weeks was getting people to know Horner.

"Most people didn't know who he was in Calgary. They had him branded as a Stelmach look-a-like which he is definitely not, so it was a huge uphill battle."

The campaign had a great online presence, Lowether said, but the ground teams, drivers to get people to the polls, put up signs and create real excitement weren't there.

"There wasn't really much as far as a ground operation in Calgary. In fact, I don't think there was much south of Red Deer."

On a percentage basis there was a huge jump in Horner's Calgary showing. The riding with one vote on Sept. 17 had 19 on the final count, the one with two votes became 43. Lowther said he believes with more time he might have been able to move the race considerably further.

Final calculation

Horner nearly doubled his support on the second ballot, but as the numbers added up to the fatal conclusion Saturday, he said it simply wasn't enough to counter Alison Redford's surge.

"Alison had her message resonate, she got here message out and that's what happens in a campaign. I have to accept that and move on."

At the Edmonton Expo Centre, Horner was surrounded by his supporters, many of whom took the news a lot harder than he did. In his hospitality area, he managed a hug, a handshake and a smile for all of them.

He said he was immensely proud of his campaign team.

"We were in a hole and we had a long way to come out of that hole. I am very pleased with what came out for us, but there wasn't enough."

Weidlich said the strategy did most of what it was supposed to do. It just couldn't compete with Redford.

"We won everywhere we wanted to win, just not in big enough numbers," he said. "I can confidently say — and we talked about this as a team — we did everything that we, as a team thought we needed to do, that we had direct control over."