I think about particulate matter a lot. It's the haze on smoggy days, the soot from a truck's exhaust, and the dust that builds up on my windowsill.

I think about particulate matter a lot. It's the haze on smoggy days, the soot from a truck's exhaust, and the dust that builds up on my windowsill.

It was also the main reason for the watery eyes and burning lungs I had on May 19 when that smoke from the Fort McMurray wildfire blew into town. The smoke packed some 263 micrograms of ash into every cubic metre of air, St. Albert's air monitoring station reports, turning the skies brown and sending asthma patients reaching for their inhalers.

Particulate matter was one of the two pollutants I wasn't able to track when I did an air quality survey of St. Albert in 2009. I didn't have the thousands of dollars I needed for a detector.

But earlier this year, I heard that the City of Edmonton had bought a cheap one called an Airbeam that anyone could borrow. I finally got my hands on it last month and set out to do the first-ever Airbeam survey of St. Albert.

Tiny bits of doom

Particulate matter refers to microscopic airborne particles such as pollen, ash and cigarette smoke. It's a major ingredient of smog, and is often so tiny that it's measured in millionths of a gram, or micrograms (µg).

The stuff we care about is PM2.5, which are particles smaller than 2.5 micrometres. You could fit at least 28 bits of PM2.5 side-by-side on the end of a human hair, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports.

Health Canada says PM2.5 is a health risk as it's small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs and blood, contributing to heart and lung disease and cancer. It also says there is no recognized safe level of PM2.5, as even a tiny bit appears to have an impact on human health.

But it's a subtle impact. A 1996 study by Harvard's Joel Schwartz found that U.S. cities experienced about 1.5 per cent more deaths per day for every 10 microgram per cubic metre (µg/m3) rise in PM2.5, for example.

That means PM2.5 can affect the health of thousands across a big area like Edmonton, says David Spink, a prominent air quality consultant in St. Albert.

“All of the scientific evidence would indicate that even at the relatively low ambient concentrations like the level we generally see in Alberta, PM2.5 does have health impacts,” he says.

At the same time, we can't eliminate PM2.5 entirely, as there's always going to be natural sources of it (e.g. dust). The impacts of it also vary between situations and persons; you're exposed to more of it if you're doing vigorous exercise, for example, and are more vulnerable to it if you have heart or lung problems.

Setting safety standards is thus a bit of a judgment call based on what's realistic and the health impacts you're willing to take, Spink says.

Canada's environment ministers have drawn their line in the sand (in the form of the Canadian Ambient Air Quality Standards) for PM2.5 at 28 µg/m3 in 24 hours – meet or exceed that, and your region must make a plan to reduce this air pollutant. They have also ruled anything below 10 µg/m3 as normal and clean.

Tracking the source

Michael Heimbinder, founder of the American non-profit HabitatMap, says his group invented the Airbeam in order to help people advocate for better air quality.

The Airbeam is one of several devices around that look to help people monitor and raise awareness of air pollution. It uses a free smartphone app that links readings taken by the device to GPS data so you can plot them on a map for others to see on the Aircasting.org website. The device costs about $250 ready-made, and you can make your own.

The one I used was a black box that sucked air past an infrared sensor to measure PM2.5 levels once a second. To use it, I switched it on, strapped it to my bag or stuck it out my car window, and hit “record” on the smartphone.

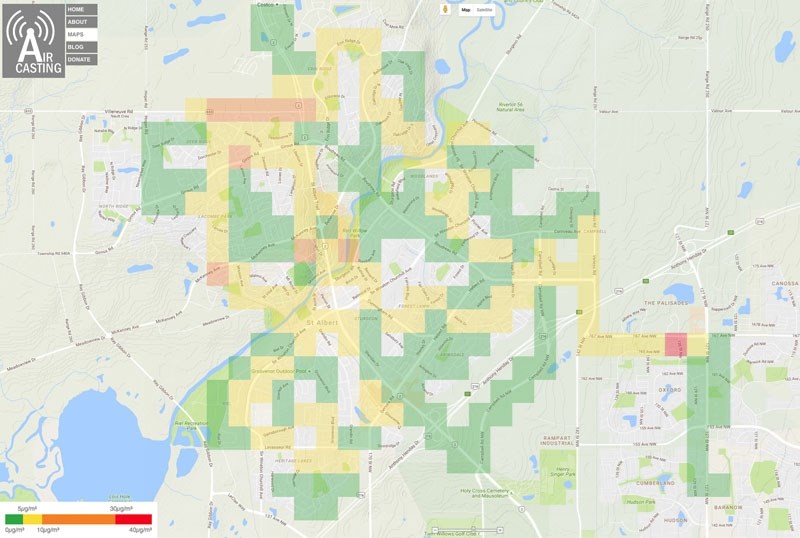

I surveyed St. Albert with the Airbeam by car on July 5 and by bike on July 6. In both cases, I tried to cover as much of the city as possible and to get readings before, during and after rush-hour.

PM2.5 can come from direct sources such as cars or dusty farms and indirect ones such as reactions between other airborne pollutants, Spink says. Combustion, particularly of fossil fuels, is a major source, as it releases PM2.5 directly (e.g. ash) and indirectly (e.g. sulphur dioxide).

The car survey happened on a very windy day, which Spink says explains why the Airbeam detected zero PM2.5 pretty much everywhere. The city's monitoring station didn't detect any during the survey either. Exceptions were St. Albert Trail (two to six µg/m3) and one spot on Campbell Road where there was a belching diesel truck (nine µg/m3).

The bike survey happened on a calmer day. Readings averaged from five to nine µg/m3, with low-traffic areas such as Oakmont reading much lower than high traffic zones like the trail. This suggests that vehicles are one of the main sources of PM2.5 in St. Albert.

Air pollution is highly local, Heimbinder says. New York researchers have determined that while half of that city's particulates come from regional coal plants, most of the rest comes from heating oil, trucks and cars. A good 20 per cent comes from pizza joints and restaurants.

Spink notes that cooking is a major source of PM2.5. If you're grilling a burger or frying fries, you're vaporizing meat and scattering oil particles.

No surprise, then, that the highest readings I found on my surveys were in or near restaurants. Levels spiked to 57 µg/m3 from about five when I passed a KFC on 167 Avenue, for example, and hovered around 250 µg/m3 inside a St. Albert burger joint at dinnertime – the highest reading of the survey.

This isn't necessarily a problem, Spink notes; there might have been a lot of PM2.5 in that burger place, but unless you were running a marathon there or had bad lungs, you probably wouldn't be affected much by it.

Industrial processes also kick up PM2.5. The Airbeam detected up to 40 µg/m3 in the Gazette's press room where we pack and print newspapers, for example, and 102 µg/m3 by the St. Albert Transit depot when I was downwind from a crew re-tarring the place's roof.

Clearing the air

With few exceptions, the readings I took in my surveys were below the 28 µg/m3 limit for PM2.5. That means St. Albert's air is pretty clean in terms of this pollutant.

Data from the St. Albert monitoring station supports this conclusion. The 24-hour average for PM2.5 (based on all available readings prior to July 31) was about six µg/m3, well below the federal limit, and much better than Beijing, China's notoriously bad air (which averaged 83 µg/m3 last year, reports the U.S. State Department).

“Relative to Beijing and China, (our air) is good, but that doesn't mean it's safe,” Spink points out.

The pollution we have is affecting our health, and we can improve our lives by reducing it. A 2013 study by Harvard University's Andrew Correia suggests that every 10 µg/m3 reduction in PM2.5 in a region adds about 0.35 years to the lives of its residents, for example.

We can reduce PM2.5 by burning less fossil fuel, Spink says. Avoid idling, take the bus and do a home energy audit, and you can lower particulate and greenhouse gas emissions.

There's also a role for regulation. Heimbinder says New York saw a significant drop in PM2.5 in recent years when it brought in stricter sulphur limits in its heating oil, for example.

Cheap portable sensors like the Airbeam could help focus efforts to track air quality. If a group were to make a bunch of them available to borrow, parents could wear them while biking or driving around town, and students could use them to track emissions from cars idling at their schools. Eventually, a map could be compiled of pollution hot spots in the city, showing where the problems are and the possible causes of them.

An average person takes about 20,160 breaths a day, Ann Brown of the U.S. EPA suggests. The evidence shows that we'll all be better off if we pay attention to the amount of particulates that are in those breaths.

See the results

To see the results of the Gazette's Airbeam survey of St. Albert, head to http://goo.gl/0PrI2J or Aircasting.org. Note that you may have to tweak the heat legend units to see everything.