St. Albert Métis residents say that it’s too soon to tell how a recent Supreme Court ruling will affect their lives.

In a ruling that prompted the many Métis leaders gathered to hear it to erupt in cheers, the Supreme Court ruled last April 14 that Métis and non-status Indians were “Indians” under Sect. 91(24) of the Constitution Act of 1867, meaning that the federal government was legally responsible for and obliged to consult with them.

The federal and provincial governments have for decades tossed the Métis between each other when it comes to who has jurisdiction over them.

That’s meant that the Métis haven’t received the basic health and medical benefits that the status Indians do, said Chris Andersen, interim dean of the Faculty of Native Studies at the University of Alberta.

Even when the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the Métis (as it did in the matter of traditional hunting rights), the provinces would all interpret those rulings differently, resulting in a hodgepodge of rights, said Cecil Bellrose, the Region 4 president for the Métis Nation of Alberta (which includes St. Albert).

“This case proves that (the federal government) does have to consult with us,” he said.

“It means a great deal to us.”

But it doesn’t mean that the Métis get a whole bunch of rights all of a sudden, he added; those still have to be negotiated with the federal government.

“There’s really not much happening yet.”

And it doesn’t make all Métis status Indians (which would confer upon them various rights), Andersen added.

“This court case wasn’t about rights. It was about jurisdiction.”

Harry Daniels, a Métis leader from Regina Beach, Sask. who died in 2004, launched this case back in 1999. He argued that the Métis were Indians under the law and should be the responsibility of the federal government. The federal government argued that the Métis were not “Indians” under the Constitution Act and not in their jurisdiction.

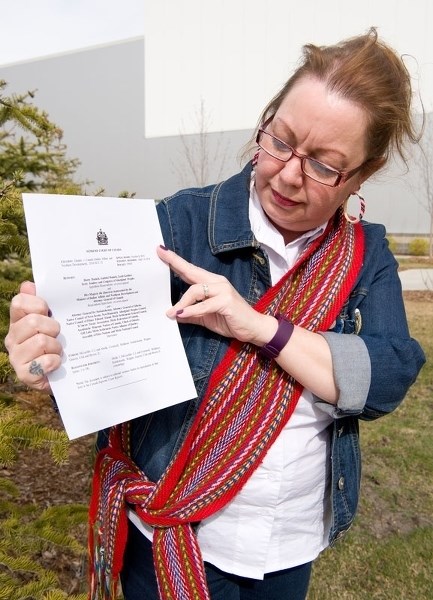

St. Albert is a perfect example of what happened as a result, said Sharon Morin of the Michif Institute, whose mother, former senator Thelma Chalifoux, worked closely with Daniels. Because governments denied they had an obligation to negotiate with the Métis, many were forced off their lands here by settlers.

“People were living on the road allowances, in the ditches.”

Writing for the court, Justice Rosalie Abella found that Métis and non-status Indians were in a “jurisdictional wasteland” where they had to rely on the “noblesse oblige” of government rather than the law of the land to enforce their rights, depriving them of many necessary programs, services, and funds.

Abella found that the federal government had previously recognized the Métis as Indians “whenever it was convenient to do so” (forcing them to attend residential school, for example) and that making them a federal responsibility would end the tug-of-war over whom the Métis should turn to for policy support.

The fact that the definitions of who qualified as Métis or non-status were ambiguous was irrelevant, she added – “Indians” in the Constitution Act clearly means all aboriginals, including these groups.

She added, though, that this would not negate existing provincial law that applied to the Métis and non-status Indians so long as those laws didn’t tread on the core of federal power over Indians.

While she approved of the court’s decision, Morin said she wasn’t sure what it would mean for the Métis.

“This might actually muddy the waters,” she said, as it may confuse the question of who qualifies as Métis.

“You can find a relative in your history that is Métis ... but have you been part of (the Métis) culture?”

There are about 31,780 Métis in Edmonton, reports the Edmonton Community Foundation, giving it the second-biggest Métis population in Canada.

Visit www.jfklaw.ca/daniels-decision for a summary of the court’s decision.