COVID @ 5

The COVID-19 pandemic changed much about life in St. Albert. This four-part series will examine the effects of those changes five years later.

When the province cancelled all in-person classes because of COVID on March 15, 2020, Kari McKnight was one of the thousands of St. Albert parents left scrambling to adapt.

“I was working full-time at the time,” she said, but suddenly she had to figure out how to work from home to make sure her kids logged into their online classes on time.

McKnight’s kids were among the roughly 1.5 billion students in 190 nations worldwide UNESCO estimates switched to at-home learning that March during the pandemic.

McKnight said the pandemic stalled her children’s education. It took her son about three years to catch up to his grade level; her daughter still struggles with math.

“We’ve had both our kids working with tutors pretty much ever since the pandemic just to keep them up to grade level.”

And teachers have told McKnight that her kids aren’t the only ones that still haven’t caught up from the pandemic.

“The feedback we always have from the teachers is, well, [your children] are below grade level, but most of the kids are.”

Measuring the gap

George Georgiou, a professor of educational psychology at the University of Alberta, has been working with Greater St. Albert Catholic Schools and other Alberta school boards to study this pandemic gap.

Based on provincial achievement tests, he found the pandemic set students back about three months for literacy and maybe seven for math. Notably, these losses were concentrated among Grade 1–3 students — reading levels in Grades 4-9 students stayed the same or slightly improved after the start of the pandemic.

Georgiou said these delays affected lower-grade students the most because those grades are when kids learn the basics of literacy and numeracy, and when you need teachers physically present so they can give immediate help to struggling students.

“In an online environment, they were not getting this.”

Inequality compounded these gaps, noted Jason Schilling, president of the Alberta Teachers’ Association. Not everyone had the computers or Internet access needed for remote learning, with some relying on paper lessons sent to students. International studies have found the pandemic caused greater learning losses among lower-income students than higher ones, Georgiou noted.

Leo Nickerson phys-ed instructor Glenn Wilson said he noticed a huge dip in student attention span once in-person instruction resumed. Students were also less fit, with most tired out after maybe five minutes of activity — likely an effect of months spent indoors learning online. He estimated about 20 per cent of his students had still not caught up to pre-pandemic fitness levels as of this year.

Wilson’s observations line up with national trends. Statistics Canada found that total daily physical activity dropped by about eight minutes for girls and about two for boys nationwide from 2018 to 2021. Screen use, meanwhile, went up, with the percentage of youths meeting recommended limits on screen time on school days dropping to 29 per cent from 41 per cent.

Bridging the gap

Wilson said he has changed his teaching strategies to adjust. He’s cut the total time he spends speaking in class to three-to-five minutes from about five-to-seven, and lectures for no more than 90 seconds at a time in between activities. He’s also made more use of short videos, and has observed that they can roughly double his students’ attention spans.

“There has to be an entertainment value to the lesson,” he said.

Georgiou said his team found they were able to reverse most pandemic-related learning losses with focused literacy/numeracy interventions and early screening. GSACRD schools had already been using both pre-pandemic, and actually saw literacy improvements during the pandemic as a result.

“The data shows right now Alberta has bounced back from the negative impacts of COVID,” Georgiou said, with literacy and numeracy levels now near pre-pandemic levels.

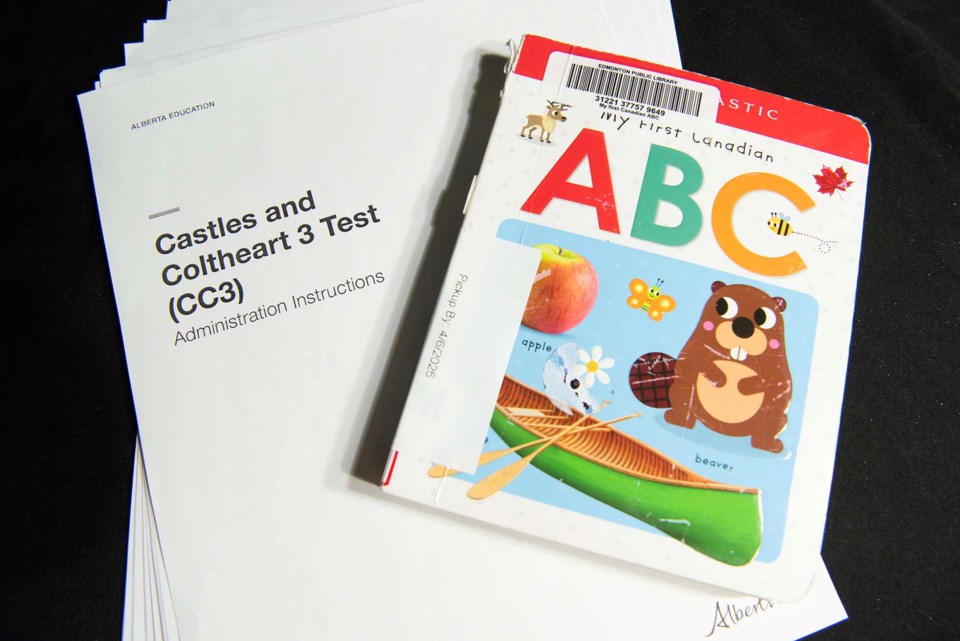

The province brought in mandatory literacy and numeracy tests (which Georgiou helped design) for Grade 1-3 students in 2022, and expanded the tests to Kindergarten last January. It invested about $85 million from 2021 to 2024 to address literacy and numeracy gaps in students brought about by the pandemic.

Schilling said these tests don’t tell teachers anything they didn’t already know, and have yet to be backed by the funds needed for teachers to address these learning gaps.

“We are the least-funded school jurisdiction in terms of spending per student in Canada,” he noted, and more funding would let schools hire the staff needed to help students.

McKnight said the province needs to step up education funding to help students bridge this pandemic gap. Her family has the means to hire tutors and other supports, but not everybody does.

“It was two or three years of really disrupted learning, and I think we kind of assumed the kids could just catch up and move on,” she said.

“I don’t know how families would do that without adequate supports.”