COST OF LIVING

The Gazette is looking at how residents are dealing with the rising costs of living in St. Albert. If you have a question on why life is so expensive, email [email protected] so it can be answered in a future story.

Life on minimum wage isn’t easy for a woman we’ll call Jane.

Jane, a St. Albert resident in her 20s who asked to be anonymous to protect her job, was working for minimum wage at a grocery store when she moved out on her own. The $15 an hour she earned wasn’t nearly enough to cover her food and rent.

“My mom had to help me buy groceries,” she said, and the only apartment she could afford turned out to be infested with bedbugs.

While she’s since moved back in with her parents and now earns $16 an hour, Jane said she still often has nothing in her bank account each month after she’s covered basic expenses. Co-workers on minimum wage tell her about living paycheque to paycheque, getting regular help from food banks, and not being able to afford cellphones or car repairs.

“It’s very stressful knowing you have to watch every penny,” she said, and stressful to walk into a store and not know if you have enough in the bank to buy what you need.

“I just wish there was a more realistic way to live in St. Albert without having to ask for help.”

Why not pay more?

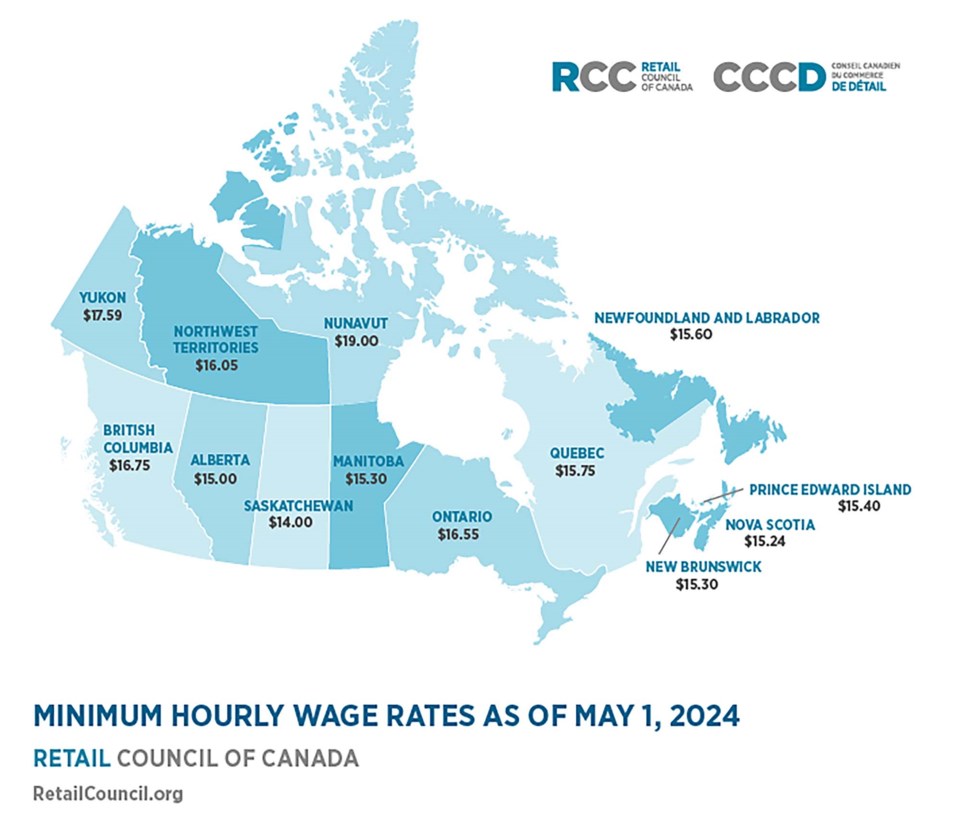

Inflation means a basket of goods that cost $100 in 2018 costs $120.24 today, the Bank of Canada reports. But if you earn minimum wage in Alberta, you’re still earning the same $15 an hour now as you did back then. Unlike every other part of Canada, Alberta has not raised its minimum wage since 2018 despite inflation. That wage is currently the second lowest in Canada, and will be tied for lowest this October when Saskatchewan raises its minimum to $15, the Retail Council of Canada reports.

The result is many families working multiple jobs just to make ends meet, said St. Albert NDP MLA Marie Renaud. The NDP has called for changes to the minimum wage several times in recent years, but the UCP government has yet to take action.

“The fact that Alberta is almost the lowest [in terms of minimum wage] in the entire country is shameful,” she said.

The Alberta Minimum Wage Expert Panel found that about 11.5 per cent of Albertans — some 227,300 people, or the equivalent of about three St. Alberts — earned minimum wage as of 2019.

It’s unclear why Alberta hasn’t touched its minimum wage in so long, said Ryan Lacanilao, economist with the Alberta Living Wage Network. Josh Aldrich, press secretary for Alberta’s Ministry of Jobs, Economy, and Trade, did not respond to emailed questions on this subject from the Gazette. Most parts of Canada tie their minimum wages to inflation and adjust them regularly.

Lacanilao said raising the minimum wage (e.g. to $23.80 an hour, which he calculates to be the minimum needed to live in St. Albert) would let more people spend money at local businesses and drive economic growth.

It would also mostly benefit families, he said. Labour statistics cited by the Minimum Wage Expert Panel show about 75 per cent of Albertans on minimum wage are older than 19 and that about 41 per cent have children.

And it would improve the province’s finances.

“When people are making more money, you get to collect more taxes,” Lacanilao said, and you don’t have to spend as much on support programs.

What about job losses?

Lacanilao said real-world studies show mixed results when it comes to minimum wage hikes and employment, with some showing increases and others the opposite.

The Alberta Minimum Wage Panel found that the NDP’s move to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour over three years likely caused around 21,000 to 23,000 job losses among those aged 15-to-24 but “no statistically significant employment changes for Albertans aged 25 and over,” who represented about 55 per cent of minimum-wage earners.

A 2014 study by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives of minimum wage hikes in Canada between 1983 and 2012 found “almost no evidence of any connection between a higher minimum wage and employment levels,” with aggregate demand being a much stronger determinant.

Lacanilao said research suggests higher wages reduce staff turnover and training costs while also boosting productivity. Higher productivity could let employers cut jobs, but higher wages typically boost demand enough to make that impractical.

Lacanilao said higher wages would not necessarily worsen inflation, noting Alberta saw the same super-inflation as the rest of Canada despite keeping its minimum wage flat. A University of Washington study found when Seattle raised its minimum wage to $15 an hour from $13.50 in from 2015-17 (and the surrounding county did not), the increase had no significant effect on food prices at local stores after two years.

Lacanilao and the Minimum Wage Panel both recommended Alberta bring in regular, predictable increases to its minimum wage by pegging it to the Consumer Price Index.

Renaud encouraged Albertans to write to their MLAs if they want to see the minimum wage changed.

Jane said a two-or-three dollar hike to the minimum wage would help her and her coworkers save money for essentials and emergencies and counteract rising prices.

“I work at a grocery store and it’s crazy the amount people have to spend to buy five or six things,” she said.

“I honestly don’t think I could afford to buy food where I work if I lived on my own.”