The debate to include members of the public in planning and development decision-making may be opened once again, in light of recent development issues.

During Monday’s city council meeting, Coun. Sheena Hughes notified council she may be bringing forward a motion to reinstate a municipal planning commission (MPC), or something like it.

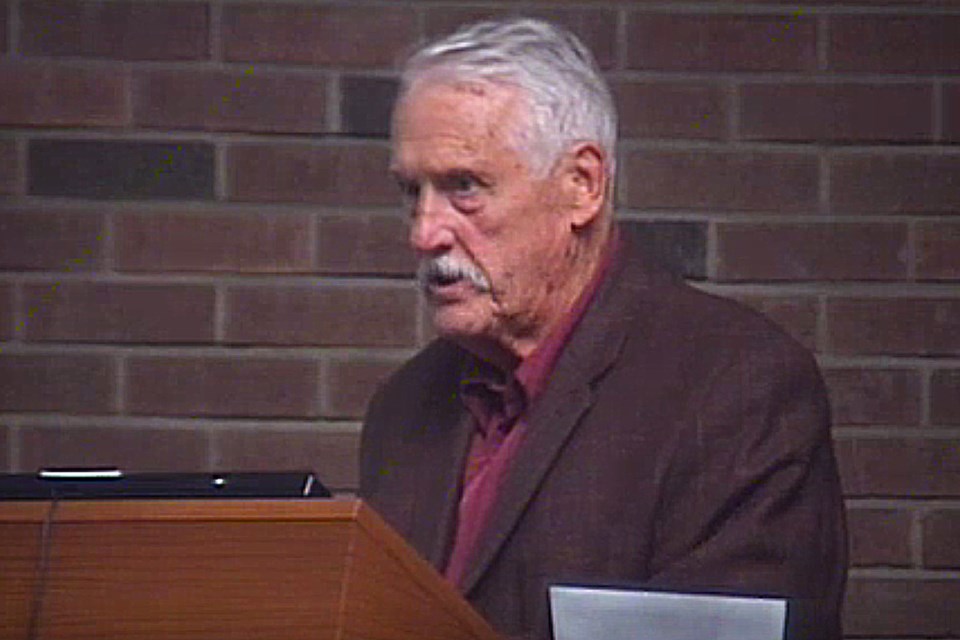

Her announcement followed a presentation from former city councillor Bob Russell, who has argued for years the MPC should be reinstated. In his presentation, he said some present-day contentious developments – such as 50 Edinburgh Court North in Erin Ridge North, where residents have raised questions of children’s safety around Lois E. Hole School – would have never been approved had an MPC been in place at the time.

MPCs are public bodies that typically help to advise council on development permits and subdivisions, sometimes making recommendations to council.

Hughes said in an interview no one cares about having an MPC until residents start questioning why they are stuck in traffic for an hour on their evening commute home.

“It’s not a sexy topic, but in my opinion, it is a responsible topic, to make sure we are maintaining the quality of life for people in St. Albert moving forward,” she said.

Due to the nature of the business, the impacts of subdivision and major development approvals may not be felt until years down the line. Hughes said St. Albert is only now starting to feel the impacts of not having an MPC, echoing sentiments expressed by Russell that perhaps an MPC could have prevented the impacts of closing part of Coal Mine Road or approving 50 Edinburgh Court North.

“That’s why I’m looking at this, is I’m seeing decisions (where) the aftermath effects of that are coming up several years after approvals take place,” Hughes said.

St. Albert used to have an MPC but its powers were stripped and handed to administration in 2005 to streamline the development process. City council formally dissolved it in 2008.

In 2017, in the early months of the current council’s term, councillors received a report on municipal planning commissions across the province. When faced with a decision in January 2018, council’s governance, priorities and finance committee struck down the idea of reinstating an MPC in a 6-1 vote, with Hughes being the sole supporter.Hughes said she is not sure if her colleagues have warmed up to the idea of an MPC, but recognized council was still fresh into their term at the time. She said she hopes with more “time and more experience,” a different decision will be reached.

“This is about making our community better. I’m trying to figure out what I would bring forward, if I do bring something forward that would have the potential of actually having the support of the majority of council,” Hughes said.

Mayor Cathy Heron said in an interview she is “not in favour” of an MPC. She added planning commissions had a place when municipalities were smaller and did not have “the qualified planning staff that we do today.”

“We have such good qualified planners that they are better equipped to make these decisions than me – I have no planning experience – or a resident,” she said. “I think the system works.”

Many large municipalities across Alberta do have MPCs, including Red Deer, Medicine Hat and Airdrie.

One developer with Averton Homes, behind the Midtown development in South Riel, said it is “the wrong time to introduce a planning commission.”

“I think we need to let the experts do their job. What’s great about this particular council is that most members of council do recognize the expertise of planners, and that’s not always common in municipalities,” said Averton president Paul Lanni.

Hughes said she respects the expertise of administration but would like an “additional set of eyes” to give input. She added MPC members are expected to go through substantial training about land use planning and the impacts of it, something council is not required to do.

Currently developers are required to hold an open house before making applications to the city, and public hearings are held before council makes any decisions. Hughes said this leaves the public out of the process for months, or even years, between the two points.

“Really when it gets to the council approval stage, the majority of the decision-making and tweaking has already been completed,” Hughes said.

Those opposed to having an MPC argue it adds an unnecessary level of red tape that delays development projects. However, the 2017 report to council on MPCs across the province said on average MPCs only add two weeks to the process. For example, Red Deer has an MPC and an average subdivision application took 45 days, while in Leduc – which does not have an MPC – it took 28 to 40 days.

Hughes said she hopes to bring forward a motion within the “next couple of months.”