A University of Alberta researcher says a cheap blue dye could help hospitals safely reuse disposable face masks during the pandemic.

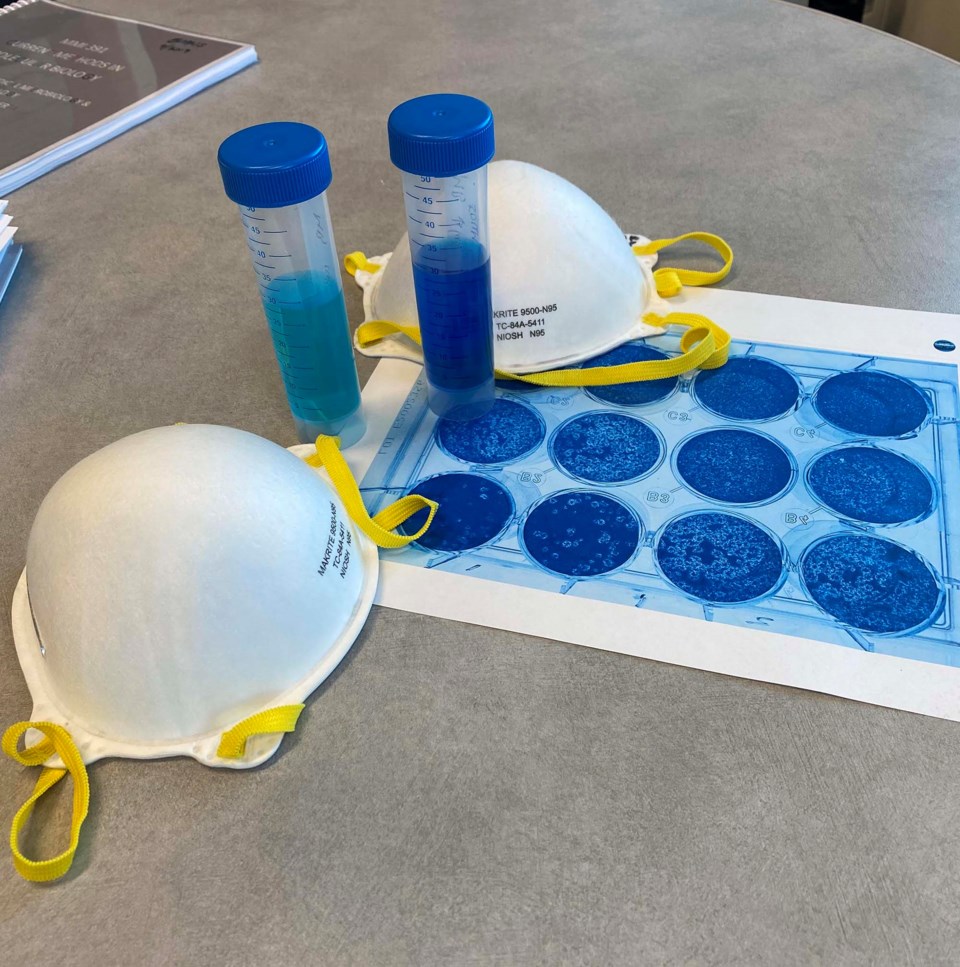

U of A virologist David Evans is one of about 50 authors on a paper published in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology in May on how a specific blue dye could kill off COVID-19 on disposable medical face masks, allowing them to be reused.

Medical masks, especially N95 respirators, have become essential tools for Canadians to protect themselves and others from COVID-19.

While there’s no longer much interest in reusing these masks in Canada (as we have lots of them), Evans said many nations don’t have the luxury of tossing out a mask after just one use. Those nations also often can’t afford the expensive equipment used to sanitize masks with hydrogen peroxide and ozone.

Evans said methylene blue is a relatively cheap dye that was once used to colour clothes and nowadays helps sterilize human plasma. It works by producing super-reactive oxygen on contact with light that kills viruses — a property the study team believes could make it a cheap way to disinfect masks during the pandemic.

Dye and light

The team ran two tests to see if the dye eliminated COVID on masks without affecting a mask’s protective qualities. Evans, as one of the few researchers with access to a lab that can safely work with COVID, was part of the first test.

Evans said he and his team applied SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID) and two other coronaviruses to six types of masks, including homemade cottons ones and N95 respirators. They sprayed the masks with the dye, blasted them with intense light for 30 minutes, and checked to see how much virus survived.

The team found the dye/light treatment disabled 99.8 to 99.9 per cent of the viruses on the masks.

“I was kind of blown away by how effective it was,” Evans said.

While the team initially started with ridiculously bright light (up to 50,000 lux, equivalent to 50,000 candles one metre away), Evans said they discovered ordinary office lighting (about 700 lux) was just as effective. Pre-treating the masks with dye/light also killed the virus, suggesting they can get ongoing decontamination by spraying the mask with dye every once and awhile.

“It’s not going to work if you don’t have the mask on right,” Evans cautioned, and the best defense is still vaccination.

The team applied the dye/light treatment to virus-free masks, then put them on volunteers and mannequin heads to test their reliability. The masks showed no loss in filtration, breathability, fluid resistance, and fit after five dye/light treatments, but lost effectiveness after five peroxide/ozone treatments.

While the dye didn’t rub off on people’s faces during the test, Evans said you probably shouldn’t hose down your couch with it unless you want a blue couch. The dye did make the masks smell “fresh” — possibly a side-effect of its produced oxygen — which was an improvement over the foul odors produced by other treatments.

The team was also able to sterilize the masks by roasting them at 65 C to 75 C for 15 minutes, with more sterilization happening at high humidity, Evans said. (Taiwan has used rice steamers to sterilize masks with this method.) Evans doesn't recommend this method, though, as mask materials started to break down at those temperatures.

Evans said the team didn’t check to see how many times they could safely reuse a disposable mask using the dye/light treatment and noted that the treatment has yet to be authorized by Health Canada.

Still, he said it could prove useful in places without ready access to masks, and has drawn interest as a less-destructive alternative to boiling bleach when it comes to decontaminating protective gear.

“If you have access to new ones, just use a new one. That way, you know they’re clean and safe.”

The study is available at bit.ly/3b7Guww.