After seven years of blindly barging his way to a bachelor of science degree, Wade Brown felt he owed his fellow graduates an apology.

"Chances are that, at some point during your time here, I have bowled you over, tripped you, or given you a good, old-fashioned caning … I'm sorry," he told his peers in a convocation speech at the University of Alberta last Wednesday.

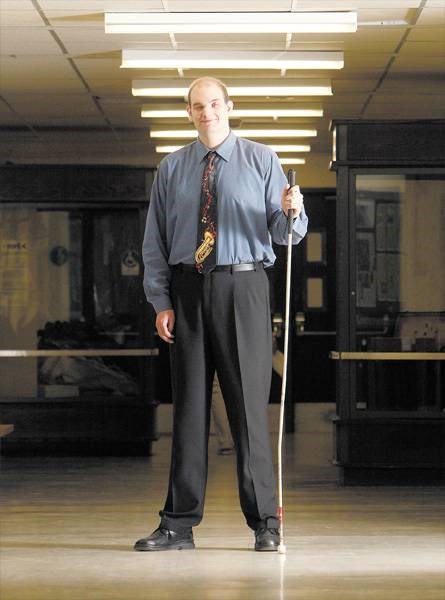

Brown's blindness isn't the only thing that sets him apart from his peers. He's also six-foot-seven. A wide swath precedes the 25-year-old wherever he walks on campus but he's still managed to clip an average of two victims a week with his cane or body.

"No one's ever said two words about it," he said with a laugh. "At the same time, you do feel kind of bad for injuring so many people."

Losing sight

Born with less than 10 per cent of his vision, Brown lost the sight in his right eye at eight years old when the retina detached. Glaucoma claimed the vision in his left eye when he was 15. This didn't stop Brown from performing in high school musicals or excelling at Bellerose's tough International Baccalaureate program. Now he's the only member of his immediate family with a degree.

"It's been a long haul but now other things can open up," said his mother Pat. "This is just another stepping stone to reach the goal and reach his full potential."

Technology

Brown's success comes thanks to the best assistive technology available along with an entire community of people, Pat said.

Over the years he's received financial assistance from the Optimist Club, the RCMP (his dad is a retired officer) and the Wayne and Walter Gretzky Scholarship Foundation.

He also had a personal aide throughout his time in the Protestant school district and a number of friends who were always there.

"It makes such a huge difference," Pat said. "Everybody has worked together for these achievements for Wade."

The key technology has been computer software that reads just about any text Brown can access with his laptop. This has made him less reliant on Braille. With professors becoming increasingly comfortable posting their material online, it has been progressively easier for Brown to access class material.

Still, throughout his university career he's had to use help such as volunteer note-takers, lab assistants and Braille transcription through a specialized university department that supports students with disabilities.

Big man on campus

When Brown first arrived on campus, a CNIB worker showed him how to get to his classes. From there it was a matter of learning his way around like any other student and seeking help when lost.

Being willing to seek help is an acquired skill that Brown has honed at the university, where he's on a first-name basis with construction workers and can summon aid just by the way he stands.

"I would go to where I knew, stand around, look lost and ask for directions. It works pretty well," he said. "There's almost always someone friendly walking by within 30 seconds."

Academically, statistics and chemistry were Brown's most challenging courses. His labs were cumbersome, requiring him to relay instructions to an aid, who then performed the experiments and described the results.

Because of the time involved in having materials transcribed, Brown took three courses per term rather than the usual five. He's achieved a 3.2 grade point average, while specializing in psychology, chosen because he's intrigued by how the brain learns.

No favours

Students with disabilities must meet the same entry requirements as other students and must meet the same standards for performance, said Brown's student advisor Jean Jackson of the Specialized Support and Disability Services branch.

Students who are disabled write their exams in a specially equipped computer lab and get extra time to compensate for clumsiness of the process.

Last year the university worked with 866 disabled students, 35 of whom were blind or visually impaired. In 1999, the university had just one student who was blind.

"They have to have persistence and they would definitely have to have a sense of humour because there are bound to be things that really do go awry," Jackson said.

Part of her work is to ensure that professors view students with disabilities as students first.

"He's a student like any other student, he just happens to be blind," Jackson said. "He's entitled to fall in love, get drunk, do whatever."

Brown's former professor and job supervisor Chris Westbury said he was surprised to find that Brown could do computer programming and complex data analysis using spreadsheets.

"He did open my eyes to what blind people can do," Westbury said. "He really did many things that I don't know how he did them."

Bright future

Brown isn't completely sure what he wants now. He's applying for graduate school for 2010 and is currently looking for a job that uses his language and data analysis skills.

Whatever happens, he feels that he's come a long way since he lost his sight 10 years ago.

"It is hard. At first when you go totally blind you start to question, what can you do, what uses can you have in society when contributing is so difficult?" he said.

"[It takes] a few years before you start developing the skills and talents that you do have. You realize there are definitely other things you can do to contribute."