Why aren't people voting?

It's the question that all electoral reforms are meant to answer.

Just 68 per cent of Canadians voted in the last federal election, reports Elections Canada – an improvement over the record low of 2008 (59 per cent) but still below the 70s Canada had prior to the 1980s. Turnout amongst youth is particularly low, notes Statistics Canada, with just half of those aged 18 to 24 voting in 2011.

"In a democracy, you want people to be sufficiently engaged so they accept the outcome of decisions," says Patrick Smith, a political science professor who studies electoral reform at B.C.'s Simon Fraser University.

Yet when Smith asks his poli-sci students if they follow politics regularly, most of them say no.

"And I say that's great, because it means old farts like me get our questions looked after!"

When you have low turnout, you get governments that don't reflect the whole population, he explains. Too much of that, and you get anger, radicalization, and candidates like Donald Trump.

That's why governments around the world have fretted as turnout rates, particularly amongst young voters, have plunged since 1945 – it's seen as a symptom of civic disengagement.

Two electoral reforms are touted as quick fixes: online and mandatory voting.

Interwebz to the rescues?

Online voting should, on the face of it, be a slam-dunk for voter engagement.

If voters aren't voting because they are too busy, out of town, or ill (the second through fourth most popular reasons why voters didn't vote in the 2011 federal election, reports Statistics Canada), putting polls an app-click away should make voting more accessible.

We can already do so much online that many think voting should be a given, says Nicole Goodman, research director at the Centre for e-Democracy at the Munk School of Global Affairs. Nova Scotia and Ontario already allow it for their municipal elections.

But online voting is so new that it's hard to gauge its impact, Goodman says. A recent study she did of online voting in Canada suggested that it caused maybe a 3.5 per cent uptick in turnout.

"There is an effect, I do think, but I think it's a very modest effect."

Her review of 47 municipal elections in Ontario in 2014 also found that youth were not actually flocking to online polls. The main users of online polls, she and B.C.'s Independent Panel on Internet Voting found, are the old and middle-aged – the same folks who already vote regularly.

"Young people actually favour voting by paper," Goodman says.

The reasons for this aren't clear, but research in Norway (which has found similar results) suggests youths may see voting as a right of passage, she says – they want the whole experience of going to the polls.

Security is a big barrier to online votes for Canadians. Elections Canada has found that while about half of Canadians believe they should be able to vote online, just one-third think it's safe to do so.

The B.C. panel recommended against its broad adoption because of security concerns, but did encourage further tests on online votes, noting how it could help disabled or out-of-town voters.

Online voting may be a tool for the already engaged, but Goodman says it could help keep those voters engaged – advance poll voting has risen as voter turnout has fallen in the last 20 years, suggesting that voters may want more accessibility in their votes.

"It definitely needs to be approached cautiously."

Vote or else?

Mandatory voting looks like the ultimate solution for voter turnout: if the problem is low turnout, just force everyone to vote.

Australia is the poster-boy here. It's had mandatory voting since 1924, and has had 93 per cent-plus turnout since 1945.

The theory is that forced votes could instil voting habits into youth and encourage residents to get engaged, says Steve Patten, political scientist at the University of Alberta. Countries with mandatory voting do see 7.37 per cent more turnout than those without, reports the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

But turnout is just an indicator of democratic health, not health itself, Smith notes. Just as taping the needle of a gas gauge in place doesn't keep a car full of gas, forcing people to vote won't keep nations full of engaged citizens.

Australia's Youth Electoral Study illustrates this nicely. This four-year national survey commissioned by the Australian Electoral Commission studied thousands of youths to find out why they weren't voting.

If mandatory voting instils citizenship and voting habits (as its advocates claim), Australia's young voters should understand the value of voting and do it even without compulsion.

Instead, the study found that about half of Australia's youth said they would not vote if it were not mandatory. Even though 82 per cent said voting was important, 66 per cent described it as boring, 60 per cent said it was a hassle, and 45 per cent said it was a waste of a Saturday.

"Many young people will vote, not because it is their right, hard-won by their forebears, or because it is their democratic responsibility as a citizen, but because they want to avoid a fine," the study said.

Other researchers have noted similar drops in turnout whenever nations drop or stop enforcing mandatory votes.

An issue of culture

There's no one cause for falling civic engagement, Patten says. People have less time to engage with neighbours and politics nowadays, for example, and their consumer identities have become more important than their civic ones. Voters might feel the electoral system makes their vote meaningless, or that none of the issues or parties excite them enough to vote.

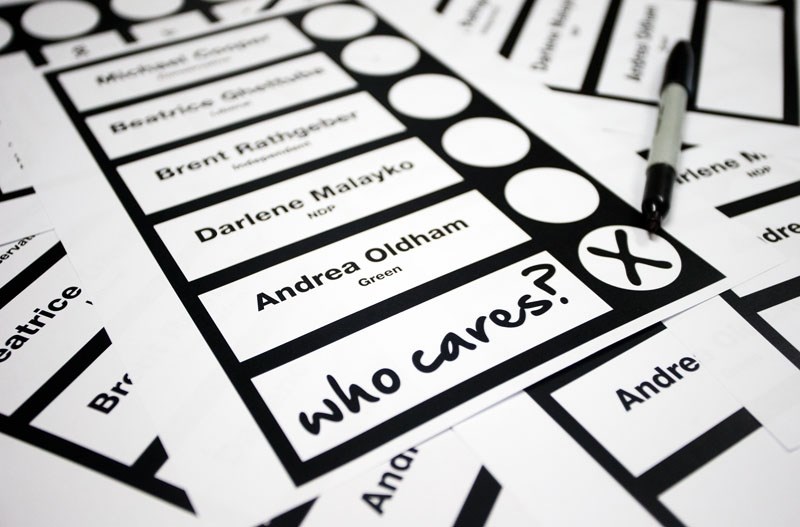

"Not interested," which includes the belief one's vote won't make a difference, was the top reason given for not voting in the 2011 federal election at 28 per cent, reports Statistics Canada.

Smith says one big issue is trust. A 2015 Statistics Canada study found that just 38 per cent of Canadians were confident in Parliament. Barely one-quarter of youths in the Youth Electoral Study found politicians were honest – a "major disincentive" for them to vote.

Institutional fixes will always fall short when it comes to voter engagement, Patten argues. What's needed is a change in political culture, one that starts with politicians signalling that they're serious about reform.

Former St. Albert MP John Williams says education about the democratic process in schools is essential for engaged citizens. The Youth Electoral Study supports this, noting that just 48 per cent of Australian youths felt they knew enough about politics to vote.

"If we want our prosperity and democratic traditions to flourish, we must teach our children how important (democracy) is," Williams says.

MPs also have to be taught that their job is to hold government to account, not to act as cheerleaders for it, he adds.

"Parliamentarians need to exercise their muscle."

Smith says giving backbenchers more power could help, as could allowing residents to petition government to debate an issue of their choice.

There's no one magic cure for Canada's democratic malaise, but a package of electoral reforms could collectively help get Canadians out to the polls and reinvigorate our democracy.