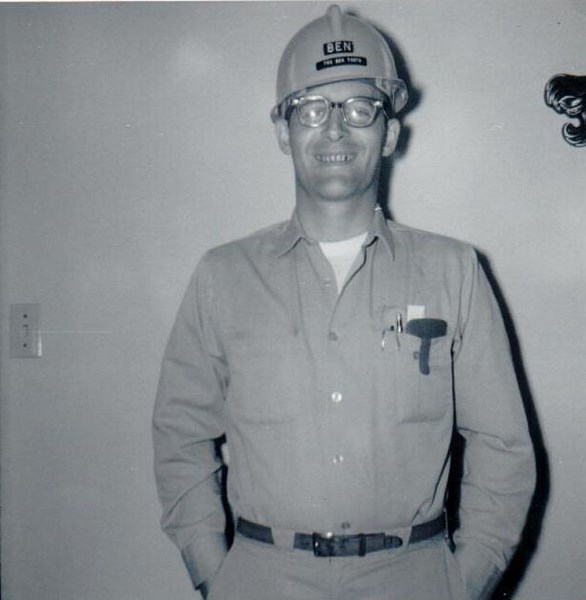

Ben Tooth was only 44 when St. Albert Place was officially opened but it would prove itself as his lifelong legacy of love for both challenges and excellence. As the project superintendent for architect Douglas Cardinal’s building, he demonstrated both his dedication in construction and in people management. It was a technically difficult effort on numerous levels that also would leave him proud for being able to accomplish something magnificent in the city that he would call home for nearly 50 years.

Ever known for his scrutinous devotion to detail and his scrupulous adherence to human ideals, Tooth died on May 6, leaving not just a family to mourn the loss of a true leader but a community of friends and admirers who knew that they could always count on him to do the job right and to do what was right.

“Ben was always a stickler for doing things right. He had high, high standards on everything,” explained Bert LaBuick, a long-time friend of Tooth’s, noting an oft-repeated mantra: “‘If you’re going to do it, let’s do it properly.’”

Born in Saskatchewan in 1939, Benjamin Tooth developed an early interest in construction while working on farms and railroads before signing on for carpenter apprenticeship classes. This was at the same time that he developed his eternal love of baseball as well. In the 1950s and ’60s, he would hone his craft while working on schools, plants and other construction projects. He also married his sweetheart Vivian during the same period. The couple would bring three sons into the world before they packed up the family and came to Alberta.

It was here that he made his name working on or supervising many significant construction projects including Londonderry Mall, the Walter C. Mackenzie Health Sciences Centre, hotels, houses, schools, factories, and even St. Albert’s famous bell tower at the foot of St. Albert Parish, not to mention St. Albert Place.

“He really had to know what he was doing,” Cardinal said. “We were all breaking new ground.”

The architect went on to say that the innovative project was the first building in the world totally laid out on computer. Because it was curvilinear rather than orthogonal, the construction team had to develop the geometry.

“It took a lot of creativity for the person in charge of construction to be able to lay it out and then build it with all of the curves. He was really committed to do something special for the community. It took all the brainpower you had.”

Tooth decided to establish monuments around the construction perimeter in order to properly layout the grid by triangulating lines onto the main site. There, it was determined that not only was the proximity to the Sturgeon River a concern but an underground river created another challenge. That was overcome by inserting nearly 600 steel piles – each 30-metres long – into the ground, something that Cardinal called a pincushion on top of which was “raft of reinforced concrete so the building wouldn’t float down the river. It was a real challenge to build on that site.”

The world-famous architect credits the success of that build to having great influence on the rest of his work, including the Canadian Museum of History.

Tooth’s son, Colin, reiterated how much of a challenge that one project was and how pleased his dad was to have achieved something so monumental to St. Albert. He said that the building just wouldn’t have been the same under anyone else’s leadership.

“There’s probably people out there that have the ability – not many at that time – but dad had the passion that nobody else had,” Colin said.

“The one thing that he said he was the most proud of that it was such a unique job that had such a unique shape that he was going to be proud of it forever, and something that he would be really proud to tell his grandkids. And he did tell his grandkids, and his great-grandkids. He was so tickled because it was in his hometown and it was such a fantastic project.”

St. Albert Place wasn’t a success simply because of a mastery of processes; it showed Tooth to be a genial commander of human forces. He was respected as much for how he commanded himself with others, something that he would even prove on the slo-pitch field, as one of LaBuick’s humorous anecdotes revealed.

“There was some kind of a kerfuffle at home plate. Another player and myself were getting a little abusive, I guess. Ben came along and stood in between myself and the umpire who had his back turned to us. I said something that was uncomplimentary and the umpire turned around and kicked Ben out of the ballpark. He hadn’t even said a word! We laughed about that for many, many years!”

“He was very much a gentleman: firm, very honest, and a great coach,” LaBuick continued.

“He was a great builder of people, if you will, because of his decorum. On and off the diamond, Ben was always a gentleman. He always wanted things to be done properly. He was a great leader in a way and he led by example.”

Colin Tooth said that his dad kept this quality with him all through his life, through Vivian’s passing, and through his own declining health over these last years. Even during his stay at the Citadel Care Centre, he maintained his idealism much to the delight of the other residents and much to the chagrin of many of the staff.

“He kept the management on their toes. He wasn’t afraid to speak his mind or speak up for the others who were too sick or too shy or too old,” he said. “From what his neighbours at the Citadel have said, they will miss his efforts in trying to take charge on most every subject, keeping everyone on their toes, while at the same time injecting some of his dry humour wherever possible.”