Prepare to be awed by stunning fabrics, soft furs, and elaborate tailoring at Musée Heritage Museum’s latest exhibit.

Powwow! Ohcîwin The Origins, which runs until Nov. 27, features a magnificent textile display of seven powwow dance styles with mannequins dressed in full Indigenous regalia.

On tour from the Red Deer Museum and Art Gallery, where it was first developed, this visual feast showcases a handcrafted mix of feathers and furs, leather and silky fabrics, intricate patterns and bold colours. Accompanying the outfits are wall panels describing the roles of various dances at powwows.

Each dance style shares teachings from the past. Each dance style has an origin story, or a specific meaning or purpose reflected in the designs, symbols, patterns, and ornaments. Essentially, regalia is a library of stories dating back centuries now carried into our modern world.

And while it might be tempting to describe regalia as “costumes,” it would be incorrect and insulting to Indigenous history, culture, and spirituality. Donning powwow regalia is a tribal honour that must be earned.

“With this exhibit, I’m going to honour my family. Since I’m going to take up space where we’ve never been before, I feel a responsibility to share real stories. People look at regalia and call them costumes not realizing how sacred they are. I love that we have the space to tell a story in all its richness and truth,” said Marrisa Mitsuing.

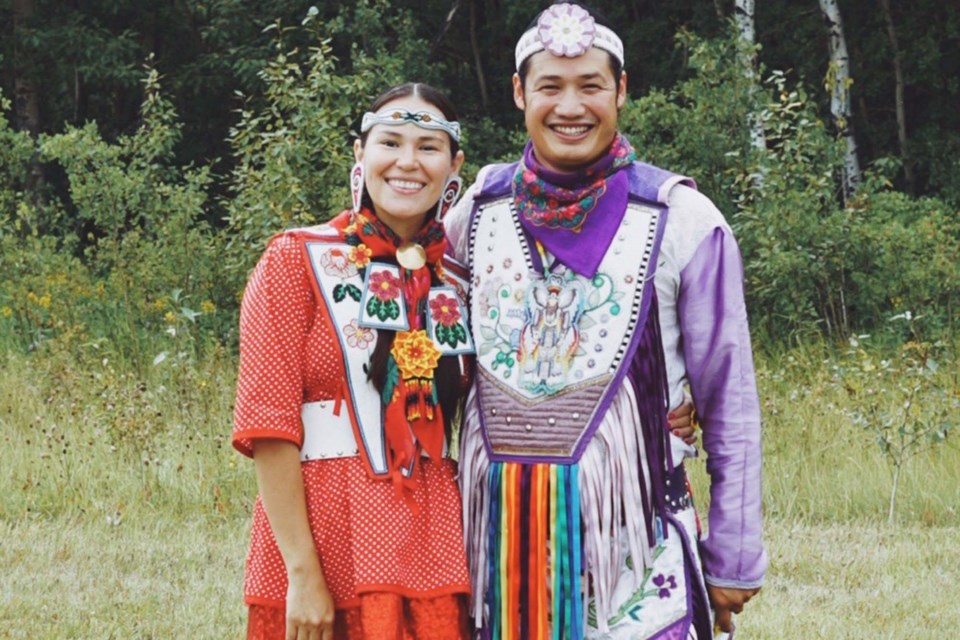

Powwow! Ohcîwin The Origins is the brainchild of Patrick and Marrisa Mitsuing, a professional artistic couple originally from Saskatchewan now living in Sylvan Lake. Patrick is a world champion powwow dancer and Marrisa creates works with diverse teams of Indigenous artists. The couple provides Indigenous teachings at schools and is contracted to give community talks on powwows.

In 2018 Marrisa submitted a proposal to Red Deer Museum to develop an Indigenous exhibit, but it took nearly a year to receive a reply. Once discussions were underway, events moved quickly and the museum team gave the couple free rein.

“They let us tell the story through the Indigenous lens. We were lucky to have travelled to different places with powwows and had learned bits and pieces,” said Marrisa, a member of Saskatchewan’s Saulteaux First Nation.

Discussions narrowed the dance list to seven: Men’s Traditional Dance, Men’s Fancy Dance, Men’s Chicken Dance, and Men’s Grass Dance. The more feminine counterparts instead are celebrated with Women’s Traditional Dance, Women’s Fancy Dance, and Women’s Jingle Dance.

Throughout the 2019-2020 powwow season, the Mitsuings met with elders and knowledge keepers across North America to record the dances’ origin stories. Meanwhile 12 artists scattered across Canada and the United States were invited to design and construct regalia.

“Finding the artists was the easiest part. We met them at powwows in past years. We had sat down and shared a meal with them, and we knew what they could do,” said Marrisa.

They fabricated dresses and capes, beaded traditional designs, sewed moccasins, constructed bustles, shaped feather fans, and created men’s accessories such as bone breastplates, belts, roach spinners (head gear), and hand-held accessories.

“They harvested feathers, quills, and fur. But it was done with care and respect for the animals.”

Upon entering the exhibit area, the first regalia visitors see is the Women’s Jingle Dance, a healing dance that originated from the Ojibwe/Anishinabe people in Whitefish Bay, Ont. In its origins, a man dreamt his granddaughter was ill. In his dream women danced in dresses that made sounds like rain, and if he sewed these dresses, his granddaughter would be healed. The pink regalia is stitched together with more than 50 gold cones making pleasant tinkles as women dance a musical side-step.

The Men’s Fancy Dance is more dramatic. The war dance originated in Oklahoma from the horse people. Dancers wear two restrictive bustles on their backs and a roach with two feathers that rocks back and forth signifying a battle, said Marrisa.

“It mimics the horse spirit and is the most athletic. You have to be very strong to dance this one. Pawnee Bill and Buffalo Bill from Wild West Shows were contracted to take dancers overseas to Europe. But the original war dance regalia scared the people and so they added bright colours so it wouldn’t be so scary.”

The Men’s Traditional Dance instead speaks of warriors who fought in skirmishes and survived. The dancer charges or completes a sneak-up on the enemy. There is also the “duck and dive” maneuver representing people attacked by arrows. Faces are painted and the regalia blends beads, porcupine quills, and feathers.

The Men’s Chicken Dance represents a warrior killing a prairie chicken during a mating dance. That night the prairie chicken visits him in a dream and asks why he was killed during a mating ceremony. Although the warrior was unaware it was a ceremony, he is tasked with completing it, or the spirit will seek revenge. In this “show-off” dance adapted from the Blackfoot Confederacy, dancers wear a porcupine head roach and pheasant tail feathers representing the prairie chicken’s antennae or ears.

Originating from the Omaha People, the Men’s Grass Dance represents scouts hidden in grass who are either tracking bison or scouting the enemy. Their moves include swaying with the grasses’ movements. Sitting Bull's band first introduced it to Saskatchewan after the battle of Little Big Horn.

The Women’s Traditional Dance originated with the Sioux people. Women stood on the outside of a ceremony circle performing a gentle two-step to support the men in the centre. Marrisa explained that symbolically women were the protectors of the circles and kept an eye out for danger watching to make sure everything was in order. As they danced gently, dresses sewn with long fringes touched the ground symbolizing a connection to Mother Earth.

The women’s rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s brought about the Women’s Fancy Dance. Women started to defy men’s laws and demanded to dance in the centre of the circle.

“They were saying ‘I can dance in the circle. I too have strength and endurance,'” said Marrisa.

Traditional dances were originally performed in suede-leather. However, a new generation of women was dancing to a faster beat opening their arms and adapting beautifully fashioned shawls to simulate the winged flight of butterflies or eagles.

“The whole exhibit took us on a journey. We had a chance to do a lot of reflecting and healing for ourselves,” said Marissa. “This whole project made me appreciate the genius of my people. If I had one day, I’d like to go back and see how they operated.”

Knowledge keeper Cecile Nepoose narrates an eight-minute video providing additional powwow information.

Museum curator Joanne White added, “This is contemporary quality work. We’re always jumping on regional stories, and this is an important story to tell. There is a resurgence of Indigenous culture, and this exhibit represents many different groups.

“As a contemporary exhibit, it’s wonderful for people in powwows to see themselves. And for people unfamiliar with powwow history, this is a way from them to learn that powwows are an important cultural institution — one that was taken away from Indigenous communities.”

Powwow! Ohcîwin The Origins is currently open to the public. A special celebration featuring drumming and dancing is planned for Sunday, Sept. 18 from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. at St. Albert Place, 5 St. Anne St. Everyone is welcome.