COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. (AP) — The Colorado Springs gay nightclub shooter had charges dropped in a 2021 bomb threat case after family members who were terrorized in the incident refused to cooperate, according to the district attorney and court documents unsealed Thursday.

The charges were dropped despite warnings from other relatives that suspect Anderson Lee Aldrich was “certain” to “hurt or murder” a set of grandparents if freed, according to the unsealed documents.

Aldrich tried to reclaim guns that were seized after the threat, but authorities did not return the weapons, El Paso County District Attorney Michael Allen said.

Allen spoke hours after a judge unsealed the case, which included allegations that Aldrich threatened to kill the grandparents and to become the “next mass killer” more than a year before the nightclub attack that killed five people.

The suspect’s mother and the grandparents derailed that earlier case by evading prosecutors’ efforts to serve them with a subpoena, leading to a dismissal of the charges after defense attorneys said speedy trial rules were at risk, Allen said.

Testifying at a hearing two months after the threat, the suspect's mother and grandmother described Aldrich in court as a “loving” and “sweet” young person who did not deserve to be jailed, the prosecutor said.

The former district attorney who was replaced by Allen told The Associated Press he faced many cases in which people dodged subpoenas, but the inability to serve Aldrich’s family seemed extraordinary.

“I don’t know that they were hiding, but if that was the case, shame on them,” Dan May said of the suspect’s family. “This is an extreme example of apparent manipulation that has resulted in something horrible."

The grandmother’s in-laws wrote to the court in November 2021 saying that Alrich was a continuing danger and should remain incarcerated. The letter also said police tried to hold Aldrich for 72 hours after a prior response to the home, but the grandmother intervened.

“We believe that my brother, and his wife, would undergo bodily harm or more if Anderson were released. Besides being incarcerated, we believe Anderson needs therapy and counseling,” Robert Pullen and Jeanie Streltzoff wrote. They said Aldrich had punched holes in the walls of the grandparents’ Colorado home and broken windows and that the grandparents “had to sleep in their bedroom with the door locked” and a bat by the bed.

During Aldrich’s high school years in San Antonio, the letter said, Aldrich attacked the grandfather and sent him to the emergency room with undisclosed injuries. The grandfather later lied to police out of fear of Aldrich, the letter said.

The judge’s order comes after news organizations, including the AP, sought to unseal the documents, and two days after AP published portions of the documents that were verified with a law enforcement official.

Aldrich, 22, was arrested in June 2021 on allegations of making a threat that led to the evacuation of about 10 homes. The documents describe how Aldrich told the frightened grandparents about firearms and bomb-making material in the grandparents’ basement and vowed not to let them interfere with plans for Aldrich to be “the next mass killer” and “go out in a blaze.”

Aldrich — who uses they/them pronouns and is nonbinary, according to their attorneys — holed up in their mother’s home in a standoff with SWAT teams and warned about having armor-piercing rounds and a determination to “go to the end.”

Aldrich’s grandparents’ call to 911 led to the suspect’s arrest, and Aldrich was booked into jail on suspicion of felony menacing and kidnapping. But after Aldrich’s bond was set at $1 million, Aldrich’s mother and grandparents sought to lower the bond, which was reduced to $100,000 with conditions including therapy.

The case was dropped when attempts to serve the family members with subpoenas to testify against Aldrich failed, according to Allen. Both grandparents moved out of state, complicating the subpoena process, Allen said.

Grandmother Pamela Pullen said through an attorney that there was a subpoena in her mailbox, but it was never handed to her personally or served properly, documents show.

“At the end of the day, they weren’t going to testify against Andy,” Xavier Kraus, a former friend and neighbor of Aldrich, told AP.

Kraus said he had text messages from Aldrich’s mother saying that she and the suspect were “hiding from somebody.” He later found out the family had been dodging subpoenas. Aldrich’s “words were, ‘They got nothing. There’s no evidence,’” Kraus said.

A protective order against the suspect that was in place until July 5 prevented Aldrich from possessing firearms, the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office said.

Soon after the charges were dropped, Aldrich began boasting that they had regained access to firearms, Kraus said, adding that Aldrich had shown him two assault-style rifles, body armor and incendiary rounds.

Aldrich “was really excited about it,” Kraus said, and slept with a rifle nearby under a blanket.

Relatives of Aldrich’s grandmother said after the suspect’s 2021 arrest that she had recently given Aldrich $30,000, “much of which went to his purchase of two 3D printers — on which he was making guns,” according to documents in the case.

Aldrich’s statements in the bomb case raised questions about whether authorities could have used Colorado’s “red flag” law to seize weapons from the suspect.

El Paso County Sheriff Bill Elder released a statement Thursday saying that there was no need to ask for a red flag order because Aldrich’s weapons had already been seized as part of the arrest and Aldrich couldn’t buy new ones.

The sheriff also rejected the idea that he could have asked for a red flag order after the case was dismissed. The bombing case was too old to argue there was danger in the near future, Elder said, and the evidence was sealed a month after the dismissal and couldn’t be used.

“There was no legal mechanism” to take guns following the case dismissal, the sheriff said.

Under Colorado law, records are automatically sealed when a case is dropped and defendants are not prosecuted, as happened in Aldrich’s 2021 case. Once sealed, officials cannot acknowledge that the records exist, and the process to unseal the documents initially happens behind closed doors with no docket to follow and an unnamed judge.

Judge Robin Chittum said the “profound” public interest in the case outweighed Aldrich’s privacy rights. The judge added that scrutiny of judicial cases is “foundational to our system of government.”

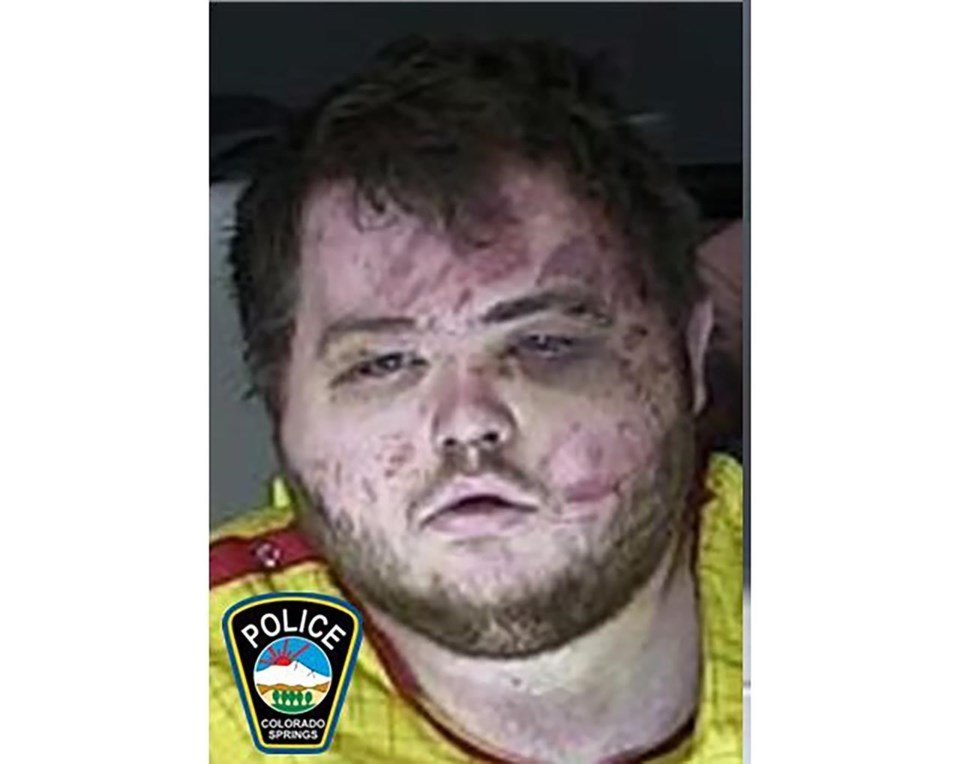

During Thursday’s hearing, Aldrich sat at the defense table looking straight ahead or down at times and did not appear to show any reaction when their mother’s lawyer asked that the case remain sealed.

Aldrich was formally charged Tuesday with 305 criminal counts, including hate crimes and murder, in the Nov. 19 shooting at Club Q, a sanctuary for the LGBTQ community in mostly conservative Colorado Springs.

Investigators say Aldrich entered just before midnight with an AR-15-style semiautomatic rifle and began shooting during a drag queen’s birthday celebration. Patrons stopped the killing by wrestling the suspect to the ground and beating Aldrich into submission, witnesses said.

Seventeen people suffered gunshot wounds but survived, authorities said.

___

Mustian, Balsamo and Condon reported from New York, and Bedayn reported from Denver. Matthew Brown in Billings, Montana, contributed to this report. Bedayn is a corps member for The Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

Colleen Slevin, Jim Mustian, Mike Balsamo, Bernard Condon And Jesse Bedayn, The Associated Press