MONTREAL — Tensions are flaring in the Mohawk community of Kanesatake nearly one month after an election was abruptly called off, leaving disagreement and uncertainty over who is in charge and how to organize another vote.

The cancellation has sparked anger, confusion and accusations of a power grab in an already deeply divided community west of Montreal, which was at the centre of the 1990 Oka Crisis. Now, it seems likely the courts will have to decide who has the authority to hold a new election.

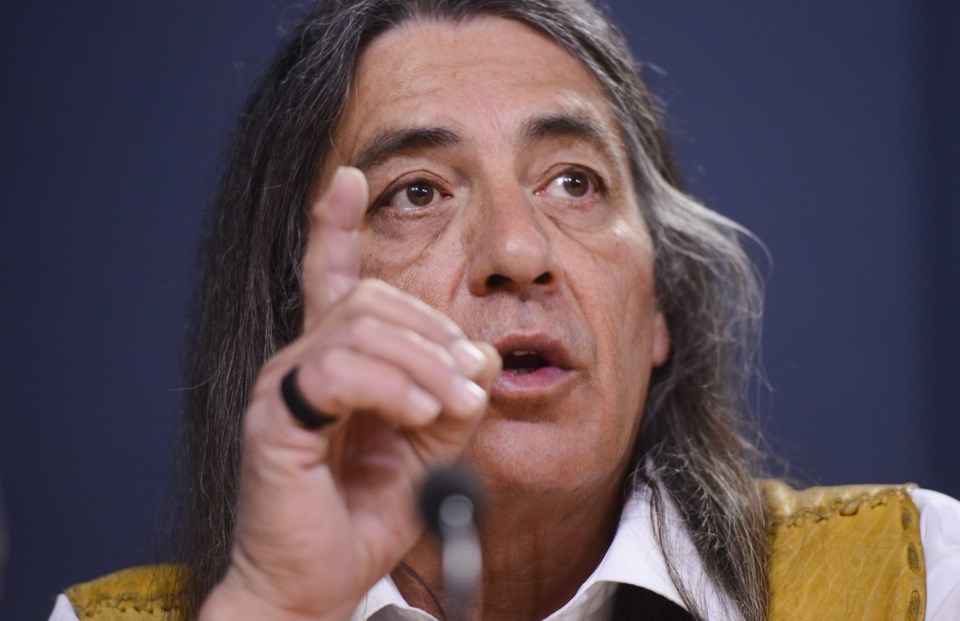

“It’s do or die as usual,” said Serge Simon, one of the incumbent council chiefs. “We always seem to be on the edge of that precipice.”

On Tuesday, the Mohawk Council of Kanesatake filed a statement of claim asking the Federal Court to declare that Simon and four other council chiefs remain in office until a new election can be held.

But former grand chief Victor Bonspille, who has been at odds for years with Simon and the other four chiefs, claims his opponents are simply trying to maintain power. “The question is, why are they so desperate to hold on to this position?” he said.

The election, scheduled for Aug. 2, was cancelled the day before by a Vancouver-based chief electoral officer, Graeme Drew, who runs a private company that had been hired by the council. In an interview, Drew said the election became “unworkable” due to flaws in the community’s electoral code.

Drew said he became concerned that band members lacked information about the vote, because there is no provision in the code to let people know an election is happening. He said he also realized late in the game that several of the candidates on the ballot were ineligible to run, including some who had criminal records, which the code does not permit.

Upon stopping the election, Drew told the council chiefs to follow a section of the code that allows the incumbent council to extend its mandate for up to six months “in exceptional circumstances.”

“Amend the (electoral) code and then start the election over with the amended code that fixes the unworkable pieces,” Drew said he had advised them.

But his decision has thrown the community into turmoil due to disagreement over whether the council has the authority to keep governing.

The Mohawk council, made up of a grand chief and six council chiefs, has for years been divided into two factions. In March, an ethics commission created by the council and composed of lawyers from outside Quebec found Bonspille and his sister, a council chief, had vacated their positions by failing to attend council meetings — a decision Bonspille does not recognize. Nobody has been chosen to replace them since then.

The remaining five council chiefs, including Simon, issued a resolution after the election was cancelled declaring that they remain in office "for the purpose of ensuring that there is no governance vacuum and for arranging and holding a new election.” But they have been paralyzed because the band's administrative staff have cut them off from council resources to avoid accusations of taking sides, the statement of claim says.

Simon, Bonspille and one other council chief were running for grand chief this year. There are about 3,000 registered Kanesatake Mohawk members, about 1,350 of whom live on the territory.

Bonspille claims the five council chiefs wanted the election cancelled to serve their own political interests. He pointed out that two previous elections have been conducted using the same electoral code, which dates from 2015.

But Simon disputes Bonspille’s claim, saying he wanted the election to go ahead on Aug. 2. A band council resolution issued by the five council chiefs states that Drew, the electoral officer, has “completely and irretrievably lost the confidence of the community.”

Amid the uncertainty, some community members moved to hire a new electoral officer to organize another election as soon as possible, a decision Bonspille supports. But the five council chiefs are asking the Federal Court to declare that only the council can hire an officer.

“In times of heightened political conflict, it is more important than ever that the rules be followed and that the rule of law can be relied upon,” reads their statement of claim.

They want the court to order that a public meeting must take place for the community to decide whether to hold an election immediately or wait to first amend the electoral code.

Indigenous Services Canada, meanwhile, has thus far indicated that the community needs to sort things out for itself. “Since the community of Kanesatake governs themselves under customary rules, ISC does not intervene in the conduct of elections and does not take a position on the cancellation of general elections,” a spokesperson said in a statement.

Drew said he faced threats during his time in Kanesatake, and feared enough for his personal safety and the safety of voters that he was working with the local security force to secure the election. “The extent of the threats and the tenacity with which some people continue to try to disrupt the process is more extreme than I've experienced in all the elections … I've done,” he said.

But Amanda Simon, a candidate for council chief who supports Bonspille, said claims of threats in the community are overblown. “To say that you’re walking on eggshells every day is absolutely false,” she said in an interview.

The current electoral code is full of holes — “Swiss cheese,” according to Amanda Simon. But like Bonspille, she accused the five incumbent chiefs of wanting to extend their mandate.

“I think there's a lot more people here who wish to have the election immediately and to have the electoral code reformed after the election,” she said.

Serge Simon, on the other hand, said many community members are afraid to speak out because of the influence of organized crime in Kanesatake. The community has recently been struggling to deal with a proliferation of cannabis stores and a controversy over illegal soil dumping on the territory.

But he said people need to get involved now, to help Kanesatake chart a path forward. If they don't, he said, "the community is going to have nobody but itself to blame."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Aug. 28, 2025.

Maura Forrest, The Canadian Press