QUEBEC — A former Quebec judge whose 2012 conviction of fatally shooting his wife was overturned last year by the federal justice minister won't face a new trial, the Quebec Superior Court ruled Friday.

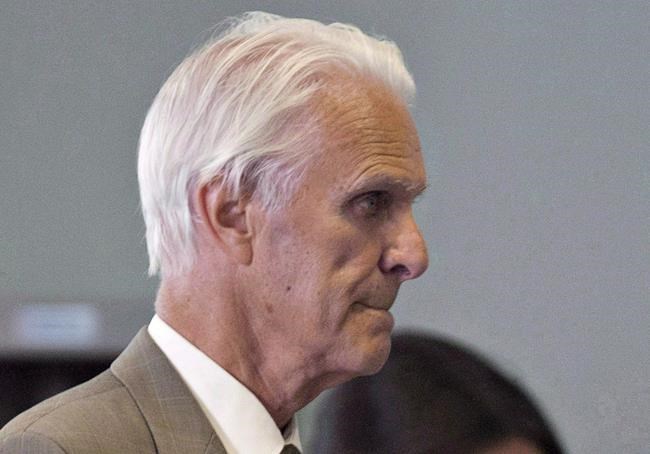

Jacques Delisle, 86, had his application for a stay of proceedings accepted by Quebec Superior Court Justice Jean-François Émond.

Delisle's lawyers argued last November that a Crown expert had made serious errors in the initial pathology report that would make a retrial impossible. They also said there had been unreasonable delays in the case.

Émond agreed, writing in a 99-page ruling that "society has no interest in a trial that will inexorably prove to be unfair. The social interest of a final judgment ruling on the merits and the process of finding the truth cannot prevail if the fairness of the trial is irreparably compromised by the fault of the state."

Following the ruling, Delisle left the courthouse in Quebec City with his family and without commenting on the decision. His lawyer, Maxime Roy, told reporters his client was relieved, adding that the most important thing is that Delisle is now a free man.

"The procedures are over for him, that is what matters," Roy said. "At 86, after more than 10 years, it had to come to an end."

A former judge on the Quebec Court of Appeal, Delisle was found guilty of first-degree murder in the death of his wife, Marie Nicole Rainville, and was sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years. His appeal was dismissed in 2013, and the Supreme Court of Canada refused to hear his case.

Delisle, who spent nine years in jail, has always maintained his innocence and said his wife took her own life.

The Crown had argued Delisle killed his spouse to avoid a costly divorce and that he wanted to move in with his former secretary, with whom he had been having an affair.

A major part of the case revolved around the angle of entry of the bullet, which could confirm or infer a suicide. Questions about the reliability of this evidence allowed for a new trial to be ordered.

"Fortunately, certain elements that had been preserved made it possible to demonstrate that (the expert) had not correctly assessed the direction of the projectile in Ms. Rainville's brain, which changed everything between the theory, was it a murder or a suicide?" Roy said outside the court.

He noted that information, had it been presented to the jury at the initial trial, could have produced a different verdict.

During the autopsy, a pathologist did not document or photograph the brain or take samples that would've shown traces of the projectile. That made it impossible for experts for the defence or Crown to do their own analysis, Roy said.

"The unavailability of this evidence is so damaging that the applicant's right to make full answer and defense is violated," the judge ruled, describing it as "gross negligence" on the part of the pathologist.

Roy said the message sent by the court on Friday is that when experts are responsible for weighing in on a case, they must preserve the evidence, especially in offences as serious as murder.

Delisle maintained that he found his wife dead when he walked into the condo they shared in Quebec City on Nov. 12, 2009. She lay on a sofa, a .22-calibre pistol at her side and a bullet wound in her head. He called 911, telling the operator that his wife had killed herself.

Rainville had been paralyzed on one side by a stroke in 2007 and was recovering from a fractured hip suffered a few months before she died. Delisle's version of events stated that his wife was depressed and took her own life using the gun that was found by her body.

The former judge didn't testify at his trial, but in 2015, he admitted in an interview with Radio-Canada that he had helped his wife kill herself by leaving a loaded gun in the home.

In April 2021, federal Justice Minister David Lametti ordered a new trial for the ex-judge after concluding a miscarriage of justice likely occurred in the case, having reviewed evidence that was not before the courts at the time of Delisle's trial or appeal.

As a result, Émond wrote, "the verdict pronounced in 2012 no longer holds."

"While this risk of miscarriage of justice rarely materializes, it cannot be ignored," Émond wrote. "This case reminds us of that."

The Crown said it will study Friday's judgment before deciding whether to appeal.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 8, 2022.

- By Sidhartha Banerjee in Montreal.

The Canadian Press