This is the sixth part of Struggling for Hope, a special feature series examining the intersections between economic instability and mental health needs. Read our introduction to the series here.

- Part 1: 'It hurts': Workers grapple with the mental impacts of Alberta's recession

- Part 2: Farmers shed light on silent fight against mental illness

- Part 3: COVID-19 robs rodeo stars of community, identity and income

- Part 4: ‘There were some dark nights’: Oilfield workers fight for jobs and hope as industry flounders

- Part 5: 'It's scary': Camp lifestyle stretches oilfield workers to the breaking point

- Part 7: 'It did get taken out on me': Domestic abuse climbs during economic downturn, pandemic

- Part 8: 'I couldn't reach him any more': Substance use rises with recession, pandemic

A week before his death, having recently quit taking antidepressants, Braden Titus was "completely and utterly broken" and experiencing a mental health crisis, says his mom Kim.

He was waiting to see a therapist when he took his own life in September 2015.

"He was awesome. He was the best guy," Kim told Great West Newspapers.

Braden, 31, was a non-judgmental guy who loved to cook and owned his own home renovation business, according to Kim. But being a small business owner was stressful, and he felt like he was falling into a "funk" due to drinking and partying, so eight months before the tragedy, he asked Kim for a recommendation for a family doctor who could get him on antidepressants.

Kim told her son she’d noticed a correlation between him “getting into a funk” and how hard and often he partied – an assessment he agreed with. He said he’d stop drinking and smoking, get on the “straight and narrow” and focus on things he loved like camping, cooking and music.

His mental health began improving after he started taking antidepressants. Kim made him promise to continue making lifestyle changes that supported his mental wellbeing, and he quit smoking and started working out regularly.

Eventually, he felt so well that he decided to quit his antidepressants cold turkey.

Kim, worried, told him it wasn’t safe to quit without a doctor’s input, but he said he didn’t feel any different when he was on them. A week later, he sent her a text saying he was “all messed up”: “Those pills hurt me more than they ever helped me,” he told her.

“He walked into the house completely and utterly broken. I had never seen him like that,” Kim told Great West Newspapers. She rushed him to the doctor, where he said he had been having suicidal thoughts. He told the doctor he would be dead if it wasn’t for his mom, dad and dog Rio.

“I don’t know – how much more at risk did he need to be?” Kim said.

The doctor prescribed new medication for Braden, scheduled another appointment a week later and gave him a 1-800 number to call in case of an emergency. It was a three-week wait to get in to talk to a therapist, but Kim said she felt Braden could wait that long with the support of his family.

Just a week later, hours before they discovered Braden had completed suicide, Kim woke up around 4 a.m. with an anxiety attack – the first of her life. Not wanting to wake her husband so early, she hung out at her house for a few hours. Finally, she woke him up and told him they needed to go check on their son. The couple rushed out of their Airdrie home and drove to Calgary.

When they arrived, Braden’s dog Rio was going crazy. Braden was already gone.

In 2015, Braden was one of 668 Albertans who took their own life, the most suicides in decades of record keeping. That grim record was influenced by mass layoffs in the oil industry as Alberta fell into a recession.

In the wake of the economic crash, Alberta’s suicide rate in the first half of 2015 jumped 30 per cent compared to the previous year. Three hundred twenty-seven people took their own lives between January and June alone. Demand for counselling also increased, with the Calgary Distress Centre seeing an 80-per-cent increase in phone calls that year.

While the suicide rate in the province has not hit that same mark since 2015, data still shows high numbers in Alberta when compared to other provinces and countries.

Alberta’s suicide deaths continue to be closely tied to the economy. For every one per cent increase in the provincial unemployment rate, 16 more people will die by suicide, according to a 2019 report from the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy.

This phenomenon is not isolated in Alberta. Simon Fraser University psychologist Dan Bilsker said across the world suicide has been closely linked to the economy.

“When unemployment rates rise, suicide tends to increase immediately,” Bilsker said.

“It's one of the strongest predictors of the suicide rates.”

Suicide impacts all demographics, but in Alberta the vast majority of deaths – 75 per cent – involve men. Almost half of those are middle-aged men between 40 and 64 years old.

LGBTQ+ youth between 14 and 25 years of age are also at higher risk, with some 63 to 67 per cent reporting having suicidal thoughts. Suicide risk is also five to six times higher for Indigenous youth compared with non-Indigenous youth.

In 2018, overall 7,254 Albertans visited the emergency department due to a suicide attempt. Despite higher death rates among men, women attempted suicide two to three times more often. In 2010, there were 1,833 hospital admissions for suicide attempts or self-inflicted injuries and women made up 58 per cent of the total; emergency rooms also saw 5,053 visits that year for attempted suicide or self-inflicted injuries, and women made up 61 per cent of those patients.

Research shows women attempt suicide 10 times more often than they complete it.

Thirty-two years ago, Leanne Heuchert felt so hopeless and lost she tried to end her life.

Heuchert still recalls that day – at just 13 years old – when she swallowed a bunch of prescription pills, panicked halfway through and called a friend for help.

Now 44, Heuchert is in a much better place. Years of mental health support have helped her to become a healthy, happy person. But when she was a young teen, she would think about killing herself.

"I would say, 'You know what, if I do this, if I cut this, I don't have to feel anything any more,'" Heuchert told Great West last year. She agreed to have her story shared again for this series.

“It was just the idea that my brain would stop making noise because there was so much going on. There was so much anxiety and there was so much sadness and just the idea that, if I do this, I'll feel that little bit of pain, but then there'll be nothing.”

Leanne Heuchert.

Leanne Heuchert.After her attempt, Heuchert was put in counselling with her family, which had already been impacted by suicide. She learned that when she was six years old, her 28-year-old brother Doug had died by suicide. Doug had passed away when she was so young her family hadn’t revealed the manner of his death until her own attempt.

“At a very young age, I saw the damage that it did to my family and I wasn’t able to understand why my family was reacting to my brother’s death the way they were. Any death is tragic, but there were a lot of unanswered questions and I believe there was a lot of guilt and confusion in my family," she said.

Don’t talk about it

One of the reasons men tend to suffer more is because they often don’t share their concerns or distress.

“They’re often trying to keep it to (themselves) – not just keep your feelings to yourself, but don’t tell your own story,” Bilsker said.

For men, sharing their feelings and problems is often considering to be a “shameful sign of weakness” in our culture, Bilsker said, whereas women share their troubles with their friends as a positive coping mechanism.

“Men are not taught really good coping, psychological coping, because collaborative problem-solving is a really important mechanism of getting through hard times in life," he said.

“Men have been taught to adopt a stoic approach as a philosophy. You don't complain, you don't whine, you do what has to be done. You take care of others in the community and take care of your family."

Buried problems can lead to serious mental health concerns and, in the worst cases, suicides. Men not taking care of themselves through their lives contributes to a lower life expectancy.

“So many people commit suicide in their 50s, 40s and 30s. The years of life lost that it accounts for is really an enormous number,” Bilsker said.

“Suicide in particular really stood out for me and some other areas where men’s health really suffers in relation to women.”

A myth around this lower life expectancy, Bilsker explained, is that men can be risk-takers who don’t take the time to do things properly. But that simply isn’t true, he said.

Self-care is also more normalized for women than men. Bilsker said a traditional male behaviour pattern is to be very fit in their younger years but making that less of a priority as they start joining the workforce, putting their overall health at risk.

To cope with problems, men are taught if they are going through a hard time, it is culturally appropriate to turn to alcohol, Bilsker said.

“That's a really dangerous psychological thing to do because alcohol just inhibits you. It interferes with your thinking and problem solving and it leaves you more likely to do something impulsive,” Bilsker said.

When the worst case scenario happens and men attempt suicide, they generally use much more lethal means.

“I think it's because by the time men reach that point, they see no hope. They don't think they're going to be rescued. They say, 'This is it,'” Bilsker said.

Experts say when men reach out for mental health help, they are often in a crisis situation, whereas women often reach out for help sooner.

While death by suicide used to be more likely among young men, that has slowly crept up to middle-aged men. Bilsker said there has been little research on why that has happened, but it could be fuelled by the rapidly changing culture we live in. In a workplace, older men can also feel outdated or less relevant than younger employees.

“These men (who) have been (working) for a long time are expendable,” Bilsker said. “I think men, historically – and it may have changed – more than women, identify their own worth with the work they are doing.”In Medicine Hat, a string of suicides struck the city this year, many from the same group of friends. Though the final death toll isn't known due to how complicated it can be to classify and report suicides, some estimates say up to seven men took their own lives over a period of several months. All were in their 30s and 40s and many had been involved in the city's hockey community.

“What the concern is, for us at this point, and where we're really super concerned, is it's a cluster,” said Cori Fischer, executive director for the Alberta Southeast Region for the Canadian Mental Health Association.

“The individuals are known to each other.”

People who know someone who has completed suicide are at a greater risk of completing suicide themselves, Fischer added.

“General research will tell you that if you know someone who has died by suicide, it becomes an acceptable coping mechanism, it becomes an option, where it may not have been considered an option before,” Fischer said.

And while surviving family members are at a greater risk, they are also left to suffer unimaginable pain and grief. Research estimates each person who dies by suicide leaves behind six or more suicide survivors – people who’ve lost someone they care about deeply and who are left grieving and struggling to understand.

Les Dunford from Westlock, Alta., lost his son Bryan to suicide nine years ago. Les is a senior reporter for Town & Country This Week, a Great West Newspapers publication.

“I think everybody probably has that same questions in their mind: 'Why didn't we see this? Why didn't we notice? What did we miss? Should we have been a little bit more in tune with the problems he was having?'” Les said.

Bryan with Kaluha in August 2007 at his Grandpa Mac's birthday party on the Dunford farm.

Bryan with Kaluha in August 2007 at his Grandpa Mac's birthday party on the Dunford farm.But Bryan always struggled with his mental health.

“We knew he had some struggles that began to show up as a boy," Les said, recalling Bryan's difficulties with his inner feelings and thoughts. But Bryan seemed to be managing his mental health well, until he started working.

“When he was out working in the working world, it just seemed like things kind of went sideways on him a little bit,” Les said.

Bryan lived in Edmonton for a while but then moved to Calgary, where Les believes he may have been using drugs a little to cope with his mental health issues. Eventually, Bryan landed in the hospital being treated for his mental health needs, and Les took him back to the Dunford farm in Westlock, where he stayed for a while.

Les said those days with him at home were some of the family’s best days with Bryan.

But Bryan moved back to Edmonton and soon ended up back in the hospital under close supervision. Les and his family would visit Bryan, signing him in and out for visits.

On June 9, the day before Les and his wife Joan’s 33rd wedding anniversary, Bryan signed himself out on his own and said he was going to Canada Place to apply for medical unemployment. Instead, he went to McDonalds for a meal, then jumped from a bridge into the North Saskatchewan River. A bystander watched him fall into the water, though his body was never recovered.

“We really have no closure and it still remains very hard for her especially. Yes, I continue to hurt too, but perhaps have come to grips with the fact that now, more than nine years later, he is for sure never returning to us, and I doubt we will ever know where his remains are,” Les said.

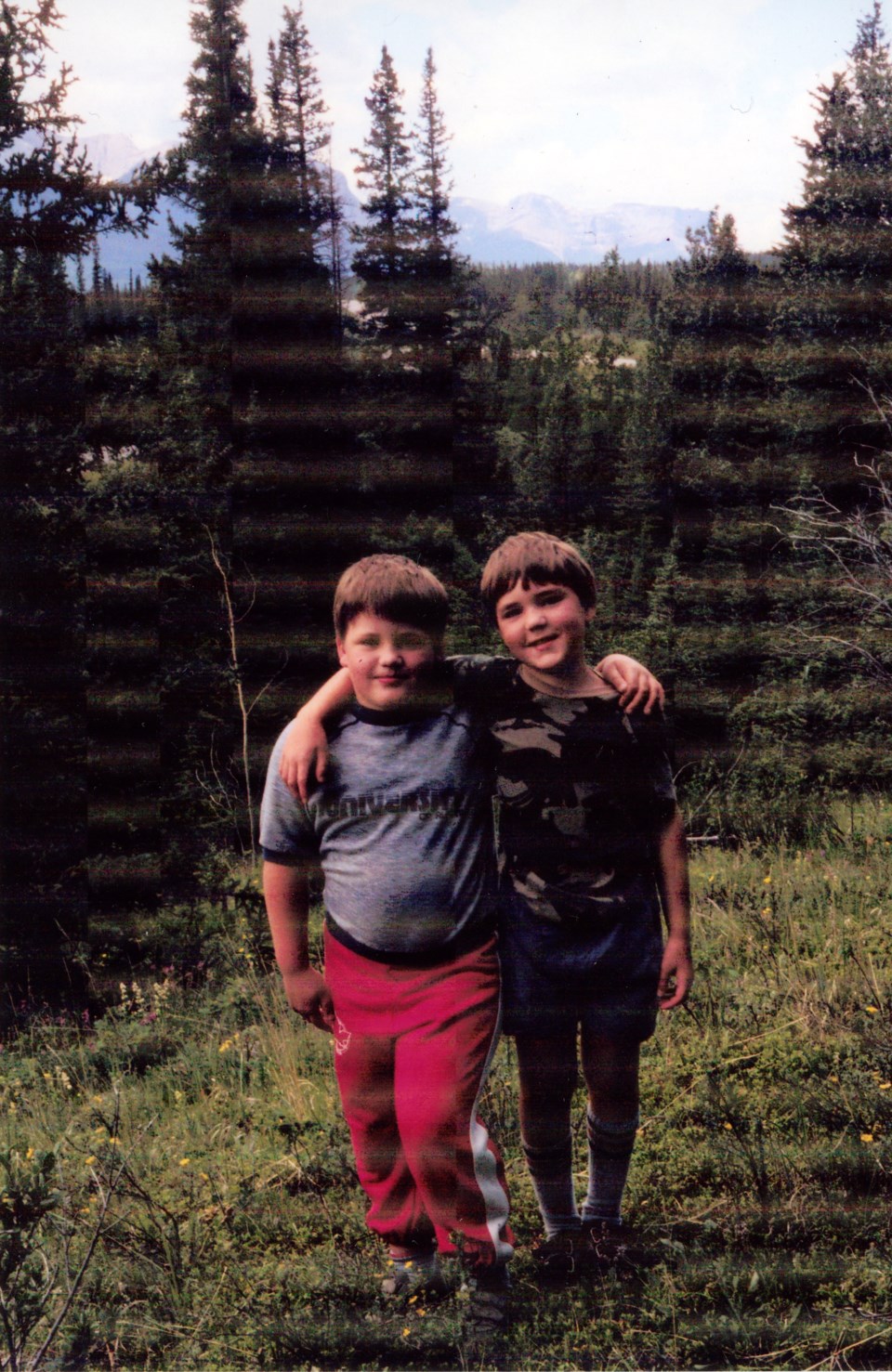

Bryan and his brother Roy.

Bryan and his brother Roy. Advocating for change

Bilsker said one of the ways to help support men and change the cultural conversation around mental health is to get away from the assumption that men are a source of suffering and pain simply due to their gender.

“We need to go away from a shaming approach. It's not really effective as a way to change people,” Bilsker said.

“We don't create a stigma around being male. We identify problematic patterns and we teach new ways of coping.”

And advocating for change in the mental health system is Kim Titus and her family, who started the Thumbs Up Foundation in 2016 to honour the legacy for her son who was passionate about helping people. The Thumbs Up Foundation is the financial sponsor for Struggling for Hope.

Thumbs Up's program advocates for structural positive changes in the healthcare system. In January, the foundation received $500,000 from the provincial government earmarked for organizations supporting mental health and addiction initiatives in Alberta. Kim said the funding is going toward a pilot project, Harmonized Health, which integrates different areas of health care and brings together professionals who don't typically work together, like doctors and therapists, in order to support people who struggle with their mental health.

The pilot project is aimed at providing new models of health care to help inform the government about the benefits of the new programs and ideas for what may need to be funded in the future.

This is the third pilot project the foundation has run.

Jennifer Henderson is the Local Journalism Initiative Reporter for Great West Newspapers, covering rural Alberta issues.

Resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health issues, you can call Alberta's 24-hour mental health helpline 1-877-303-2642.

The addiction helpline can be reached at 1-866-332-2322 and is also available 24/7.

If you are having suicidal thoughts or you know someone who is, you can get help by calling the Canada Suicide Prevention Service at 1-833-456-4566 or by texting 45645.

Alberta's community and social services helpline can be reached by dialing 211. The 24-hour distress line is 780-482-4357 (HELP).

The rural distress line for northern Alberta is 1-800-232-7288.

If you or someone you know is at risk of an immediate crisis, call 911.