If you’ve ever looked at the map of Sturgeon County, you might notice a few odd names.

Why is there a place named after a hat, for example? What’s Volmer, and why does it appear to be an empty field? Who was the poor sod killed at Deadman Lake? And is Bon Accord really a “good agreement”?

There’s a story behind every place name in Sturgeon, the beginnings of which came long before the county. As we wrap up Roots of History, the Gazette digs into those names on the map and finds a wealth of knowledge.

Places, people, and things

Our tour guides on this journey are the historians of the Alberta Geographical Names Program, who are the official keepers of place names in this province and the ones you write to whenever you want to rename a local mountain.Ronald Kelland, co-ordinator for the geographical names program, said there are some 8,912 named places in the province, the backstories for most of which can be found in Place Names of Alberta.

“Place names are just a fascinating concept in general,” Kelland said, as people love the stories behind them but rarely think about them unless asked. They’re also often tough to explain, as in many cases no one bothered to write down those explanations.

No one’s quite sure why surveyors named Lily Lake (east of Legal) as they did, Place Names reports, and if there was ever a point to the name Lostpoint Lake (northeast of Gibbons), it’s been lost to history. The origins of Fairydell (north of Legal) are as mysterious as fairies themselves.

Fortunately for us, most of Sturgeon’s place names have well-documented origins.

Namao’s post office was named in 1892 after the Cree word for lake sturgeon, which frequented the nearby Sturgeon River, Place Names reports.

Namao Museum historian Betty-Lou Kindleman said Carbondale got its name from the copious amounts of coal in the region, much of which was sticking right out of the riverbank.

“I’m sure the settlers were more than ecstatic to find it,” Kindleman said, as it helped keep their homes warm.

Redwater was also named for a natural resource, Place Names reports – ochre, which gives the water in the nearby Redwater River a reddish tinge.

Several names are translations of Cree ones, Place Names reports.

Big Lake is English for mistihay sakihan, or “large lake”, for example, while “Manawan” Lake north of Morinville is Cree for “egg-gathering place” – fur traders often went there to get duck eggs. Rivière Qui Barre was initially settled by francophones, who translated the Cree name of a nearby river, Keepootakawa, to “river that bars the way” – a reference to the fact that it was too shallow to drive logs across.

The Sturgeon River does have a Cree name – Mi-koo-oo-pow – but that translates to “red willow,” which is found in abundance along it. Place Names says it was cartographer David Thompson who dubbed it the “Sturgeon Rivulet” in 1814 – a reference to the fish in it.

Many locations are named for people and families.

Calahoo refers to William Calahoo, an early Métis settler in the area, while Gladu Lake west of Villeneuve is a tip-of-the-hat to the Gladu family, who lived around it around 1855. Kimura Lake west of Redwater was named in 1984 after the family of Toyomatsu Kimura, a Japanese man who homesteaded and farmed there for about 50 years.

Legal and Morinville were named after Archbishop Émile-Joseph Legal and Father Jean-Baptiste Morin.

Morin was recruited by Bishop Grandin to bring French Catholic settlers to western Canada, and drew some 2,500 to the Edmonton region between 1891 and 1899, said Legal historian Ernest Chauvet. Those settlers established colonies at Edmonton, St. Albert, Morinville, Fort Saskatchewan, Stony Plain, Beaumont, Villeneuve, Rivière Qui Barre and Vegreville, historian Alice Trottier writes.

Legal came to St. Albert as an assistant to Grandin, who had ruined his back through years of travel, Chauvet said. Legal was widely respected as a man of the people, and was also an architect, designing the basement of the St. Albert Parish church and many other structures in this region.

Legal established the church and parish that is now the Town of Legal around 1899. He also created a parish at Villeneuve in 1897 at the request of its residents, who didn’t want to walk all the way to St. Albert to pray, Black Robe’s Vision reports. Villeneuve was originally known as St. Pierre’s, but rebranded in 1900 when it got a post office to honour Frederic Villeneuve, the area’s representative on the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly.

Gibbons was initially dubbed Astleyville by its first postmaster, Henry Astley, in around 1904, writes historian Harry M. Sanders. When he left, residents asked for a new name like Sturgeon Bridge or Valley – the post office chose Battenburg. Its current name comes from area farmer William Reynolds Gibbons, who convinced a railway company to change its route so it wouldn’t cut his farm off from the Sturgeon. The company named the local rail stop after him in 1920.

Strange tales

Some of the place names in Sturgeon require more explanation than most.Take Deadman Lake, which is just north of Alexander (itself named for its founder, Chief Alexander Arcand). Sir Samuel Steele reports that the name refers to a Cree man who was killed there in a drunken row, and that it was known to the Cree as hahpeukaketachtch, or “man-who-got-stabbed,” Place Names reports. Deadman Lake should not be confused with Deadman’s Lake near Provost, which is named for an ex-cop found dead there in 1896.

The community of Fedorah is and isn’t named after a hat. Place Names says the area’s first postmaster, Albert Leroy, named it Fedora after Fédora, a popular play by Victorien Sardou. The post office inexplicably added the “h” to the name later. American haberdashers invented the fedora hat to exploit the play’s popularity, but it’s unclear if that hat was actually worn in the play itself, says hat historian J. Bradford Bowers.

Bon Accord’s name is French but comes from Scotland, explained Mayor David Hutton.

“The Bon Accord name is actually the motto of the City of Aberdeen in Scotland,” he said, and was picked back in 1896 when Aberdeen expat Alexander (Sandy) Florence suggested it as the name for the region’s school board.

“Bon Accord” was the password used during the capture of a castle in Aberdeen during the wars of Scottish independence, Place Names reports. The official toast of Bon Accord is “happy to meet, sorry to part, happy to meet again.”

If you’re looking for Volmer, good luck – like many localities, it’s still on the Sturgeon map, but in practice no longer exists.

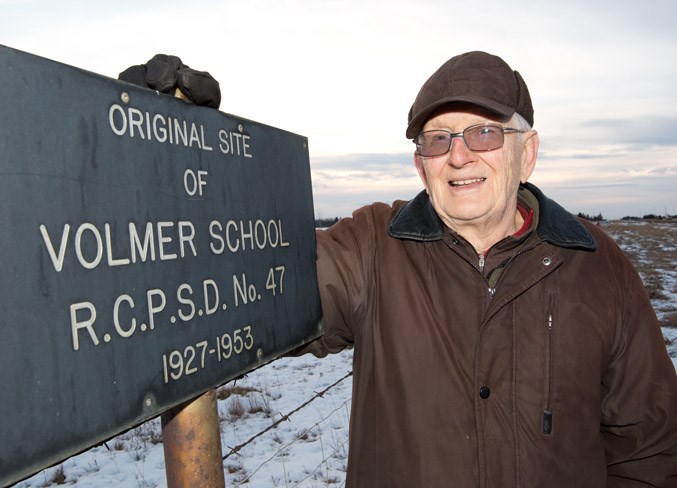

Farmer John Bocock went to school there, and said it once stood about a mile west of the Highway 2 and 37 intersection. Look carefully, and you’ll spot a metal sign on the south side of the highway indicating the location of the old Volmer School.

Volmer was created as a result of the expansion of the railroad towards Athabasca in 1908, reports Black Robe’s Vision. It was named after farmer Joseph Vollmer, who sold the railroad the necessary land. At one time, Volmer had two grain elevators, a two-storey store, and a stockyard. Bocock said the one-car diesel train that serviced the area was known as “The Skunk” due to the smell of its exhaust.

Volmer went into a steep decline when one of its elevators burned down around 1945, Bocock said. He was one of the last students to graduate from the school before it went, too. When the post office shuttered in 1968, “that was the end of Volmer.”

Names of the past

Like Volmer, the origins of most Sturgeon County place names are likely a fading memory to most residents.While Bon Accord does have an official tartan, it doesn’t have a big Scottish presence today or any official link to Aberdeen, Hutton said.

“Everyone says they’re from Bon Accord, but the terminology has lost a lot of its meaning.”

Kindleman said she recently dropped a note on the origins of Namao’s name in the community’s newsletter, and always looks up the stories behind place names whenever she goes travelling.

“It connects you with the ancestry,” she said, noting that many refer to the initial settlers of a region.

While their meanings may have faded, the names of Sturgeon County’s communities are still a source of pride for those who live in them.

“I don’t think anyone has a ‘Namao’ address anymore,” Kindleman said, “but do we all think we still live in Namao? You better believe we do.”