If the Canadian electoral system is set to change, will voters get a chance to have their say on the changes? Should they?

The majority Liberal government has promised that the 2015 federal election will be Canada’s last to be conducted under a single member plurality system, commonly called first past the post.

While national engagement of some kind has been promised, some are already pushing for the final decision to be in the hands of Canadian voters by putting the issue to a vote in a national referendum.

In the House of Commons, the charge for a referendum is being led by the Conservatives.

“If you want to change the rules of a democracy, all Canadians must have a say,” said St. Albert-Edmonton MP Michael Cooper, who has recently sent mail to constituents highlighting a petition asking for a referendum.

Cooper’s preference is to keep the current system. But, if the Liberals persist in proposing reform, he is insistent it should go to a referendum.

“I’m not optimistic that this government is interested in hearing what Canadians have to say,” he said.

Former St. Albert MP Brent Rathgeber said he’s not sure if there should be a referendum or not, but predicted that it wasn’t likely one would be held.

“I know they’re not going to put it to a referendum,” he said.

Rathgeber hesitates to say there should be a referendum because he thinks that such votes should be held on clear, binary issues – for example, a vote to close the city center airport in Edmonton, or not. He’s not sure if a referendum on electoral systems could be held in such clear terms.

He suggested, referencing National Post columnist Andrew Coyne, if there is to be a referendum, it should be after a new system has been tried, so people know what they are voting for or against.

It’s still not clear which way the Liberals will jump on the issue of a national referendum. Democratic Institutions Minister Maryam Monsef hasn’t explicitly denied the repeated requests for a referendum, sticking with lines like the one from the Feb. 1 round in the House of Commons, where she said “we will undertake a process to consult with Canadians in a meaningful and thorough discussion about ways to modernize our democratic institutions.”

So far, the Liberals have announced they’ll convene an all-party parliamentary committee and have a national engagement process.

Rathgeber is hoping they’ll go to experts rather than rely on politicians.

“I really hope that they farm it out. I really hope that they bring together a committee of academics and political scientists and statisticians and people with no skin in the game, other than that they’re Canadians and they want a fair and workable electoral system,” he said.

While St. Albert voters will remember local plebiscites as recently as the vote on Servus Place, national referendums have been few in Canadian history.

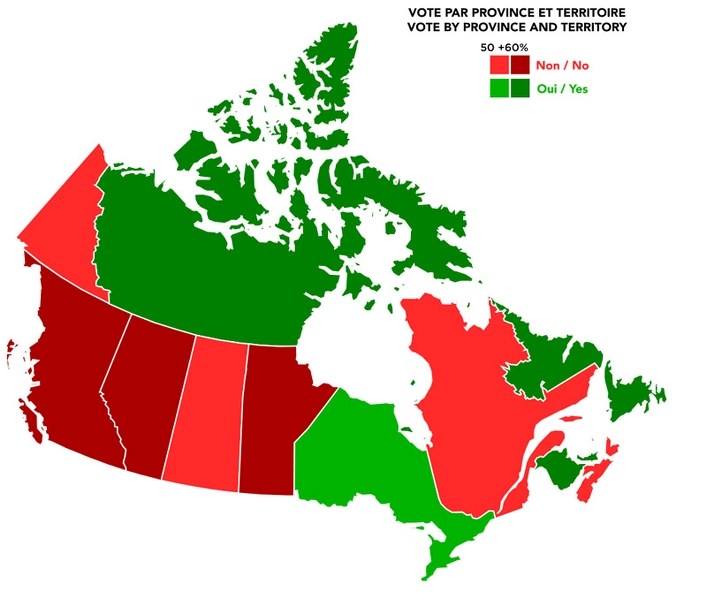

The last national referendum was in 1992 on the Charlottetown Accord, which would have updated the Constitution had it passed.

During the Second World War, there was a plebiscite on conscription. There was also a referendum on the issue of prohibition in 1898. All three were considered non-binding.

And while the 1995 Quebec referendum over that province’s future with the country lingers in the national memory, it’s just one of several provincial referendums that have been held over the years. Referendums have even been held on the topic of electoral reform in some provinces, like in B.C., Ontario and Prince Edward Island.

Steve Patten, a political scientist from the University of Alberta, isn’t sure that a referendum is necessary.

“It appears on the surface, when you don’t think about it, that the most democratic way to make a decision is to have a referendum, but it’s not necessarily the most democratic or most appropriate,” Patten said.

He cited the citizens’ assembly that was created to study and develop electoral system reform in B.C. where a man and a woman were randomly selected from every single constituency. Patten said the results of that assembly’s work, or any randomly selected body, would likely be the same as the majority of the population would make if the same process of education and debate could be undertaken.

He said many feel the referendums that were then held in B.C. didn’t allow for the kind of robust debate that should have happened because of the rules the government put in place.

“I’m not sure that the referendum in which it failed was any more democratic than the citizens’ assembly,” Patten said.

“I think the referendum is too blunt an instrument,” he said. “With electoral reform, I think the decision process requires sort of a multi-stage and deliberative process where people can think about principles, can articulate a vision, can hear what other people think and respond to that.”

Melanee Thomas, a political science professor from the University of Calgary, would advise the government against changing the electoral system without having a referendum.

“Politically I wouldn’t recommend it,” she said. Thomas said she does think a referendum is necessary.

An online poll conducted in late January by Insights West suggested 37 per cent of the 1,002 people polled felt there should definitely be a referendum if there’s a proposed change to the electoral system. Another 28 per cent thought it probably should be put to a referendum. About 18 per cent of people were not sure, while the remainder thought a vote in the House of Commons was likely enough.