Su Kerslake knows the value of reading. It opens up the world to everyone so that they can learn, understand and grow.

"Literacy is my life – my training, my career, my passion," she wrote on a recent blog for A Better World, an international development organization headquartered in Lacombe, 90 minutes south of St. Albert.

The St. Albert resident is a literacy consultant for Edmonton Public Schools. Her job is to offer professional development to teachers, so it's a job that gives her the chance to help a lot of people develop those critical skills of reading and writing. She teaches the teachers how to make that job easier.

Helping people learn how to read and write is so important to her that she jumped at the opportunity to travel halfway around the world so that she could offer her unique understanding of helping people where it's needed so very much.

Last month, she and two dozen others (including 19 teachers) spent two weeks in Africa, trying to make a difference on the Two Countries/One Voice teaching tour.

"The purpose of these teaching tours is to train Kenyan teachers to deliver better teaching methods to their students," explained Eric Rajah, the co-founder of A Better World. "One of the needs that Kenyan teachers face there is that they don't get PD [professional development] days like we get here. Sometimes they could go for years without any PD days, just because of money and budget."

A Better World has been filling in the gaps with these transatlantic professional development tours for five years, helping teachers in various regions but primarily in schools that the organization built and has been operating for two decades.

The first lesson

The tour took the group to the Rift Valley, three hours north of Nairobi near Mt. Kenya National Park in the central part of the country.

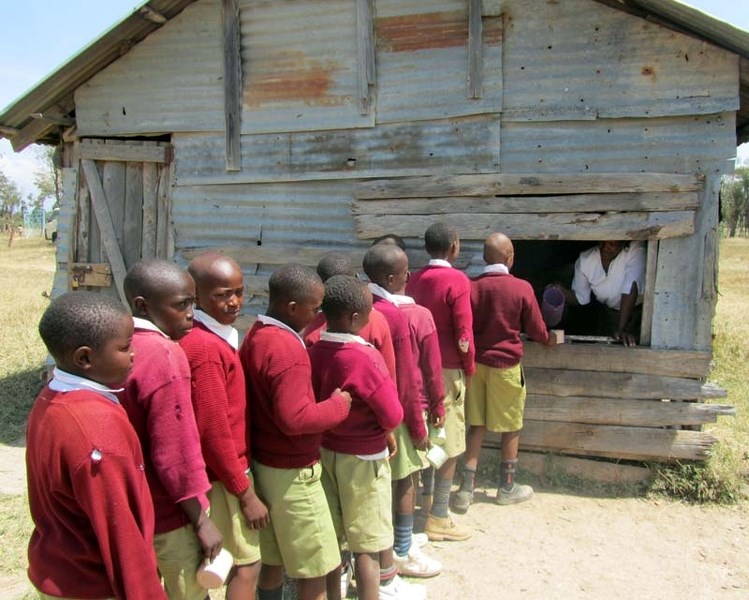

Rajah also accompanied Kerslake and the others of the group on the trip. They spent the first half of July offering workshops to the teachers at Male (pronounced Mah-Lay) School and then watching them implement their new skills with the students. The primary and secondary schools have approximately 500 students but the resource library can't match those numbers.

"The Grade 1 that I was associated with usually has about 40 kids in it, and they've got 13 textbooks. That's all they have for resources. With that, they're trying to give the kids the skills to survive in the world."

Kerslake said that western educators like herself are very much resource-oriented. That means they can hand out study sheets and assign pages of homework. Teachers can use projectors for electronic presentations. These are all moot in areas that can't afford books and where the school has no electrical outlets. The walls don't even keep out the blowing dust so the teachers have to drape plastic across the gaps. Running water is a pipe dream.

This required her and the others to go back to basics in a big way. She came to understand that the students were very good at phonics, a method of teaching language based on the ability to hear, understand and combine the individual sounds within words. There was only one problem with this.

"They didn't have any understanding. That's where I decided to go in with my literacy professional development … let's teach kids to comprehend what they're reading, not just to be able to say the words," Kerslake said.

She admitted that this was a big challenge, essentially working from a clean slate. The books were too advanced for the kids anyway, so she had to talk the teachers through a language experience or shared writing approach. They accomplished this by taking the topic words from vocabulary lessons and putting them into context with the reading materials.

What she witnessed was that the group of 40 shared the 13 books, making the best of a limited resource. In some ways, the kids needed a lot of help but in other ways they had already figured out the best way for them to learn.

"They do a lot of group recitations. They would just repeat without really thinking about what they were reading or what they were doing at all. I quickly realized that to go from group recitation to 'try and talk with your partner about what you're reading and what you're thinking' was just too big a step. How to really break it down into those small, small, little steps because it's changing the entire culture of kids just repeating or doing what adults want them to do."

She elaborated that one of the popular sayings with North America educators is "whoever is doing the most talking is doing the most learning."

"This is based on a social constructivist view of education that students can't just be told information. They need to process their learning by doing something with it: discussing, creating, representing, applying, etc. It also causes teacher roles to shift as they do not control all the interactions within the classroom."

The opposite, however, was the case in Kenya where the teachers talked the most. She figured that the students might appreciate having more of a chance to speak.

"We thought that the Kenyan students would eagerly embrace opportunities to 'turn and talk' with a partner about the concepts the teachers were teaching. We thought this strategy would be a good match for them as they tend to be a very sociable, talkative culture. However, this was such an extraordinary instructional method to the students and teachers that the students, unaccustomed to interacting during class time, quickly got out of control. Instead we talked with the teachers about the value of including student talk and the eventual goal of how this could look in their classrooms."

Doing more with less

During her time at the school, she often observed large groups of children happily playing on their own, nary a toy among them. At another point during a class, she introduced a few crayons as surprises for some students that had finished assignments. The other students, however, saw the gifts and became overly enthusiastic to say the least.

"We had members of our group that were doing co-operative games like Red Rover. One woman was very brave and brought recorders. She taught the Grade 5 class how to play. At the end, she said to me, 'Whoever thought that bringing 60 children recorders in a concrete room would be a good idea?' Her head was ringing for about three days after!"

This led to an extended discussion about stuff. Kerslake and the others brought gifts of things that they all thought the villagers would appreciate, like toothpaste. A lot of adults only had a few teeth, however. She also said that most of them had never left their little community or even had much concept about the shape of their country because they couldn't travel anywhere.

"One of the teachers said to me, 'I heard in Canada, every family has a car. We're lucky if one family in our whole community has a car.' I said, 'Actually, my family has four cars.'"

This led the African teacher to conclude that Canadians are "very wealthy," which in turn made Kerslake reflect about the meaning of the word wealth.

"We have a lot of stuff. I don't know if we're really that rich, because these guys have relationships," she said. "There's no kid there on anti-stress medication. My idea of what poverty is and what riches are has really changed from being there."

For the most part, the most effective tools for helping the kids learn are a bowl of porridge for each child and an ample supply of clean drinking water. The school now has a well, thanks to A Better World. This makes it a central hub for the community.

The organization is also keen on helping them to grow their own food rather than rely on porridge rations.

"[Rajah] says that's giving them a handout, and that's not what they need. They need a hand up. Instead, he's gone into these schools and helped them establish gardens," she explained. The produce would then feed the kids or be sold as excess to help the school to support itself.

"It's hard to learn if you're starving. It's hard to learn if your family's dying around you based on starvation and dehydration. That's the number one thing."

Visit www.a-better-world.ca for more information.