Canadian birds are infested with feather mites, and that might be why their feathers look so good, a new study suggests.

University of Alberta biology professor Heather Proctor co-authored a study in Molecular Ecology last week on how mites help clean bird feathers.

Feather mites have long been seen as parasites of birds, with bird researchers blaming them for chewing holes in feathers, said Proctor, who studies mites. But mite researchers have long suspected that the mites (microscopic eight-legged creatures) were innocent, and that the true bad guys were feather lice (macroscopic six-legged bugs), as they often saw birds that were loaded with mites but had good health and fabulous feathers. Thing was, no one had actually tested that theory.

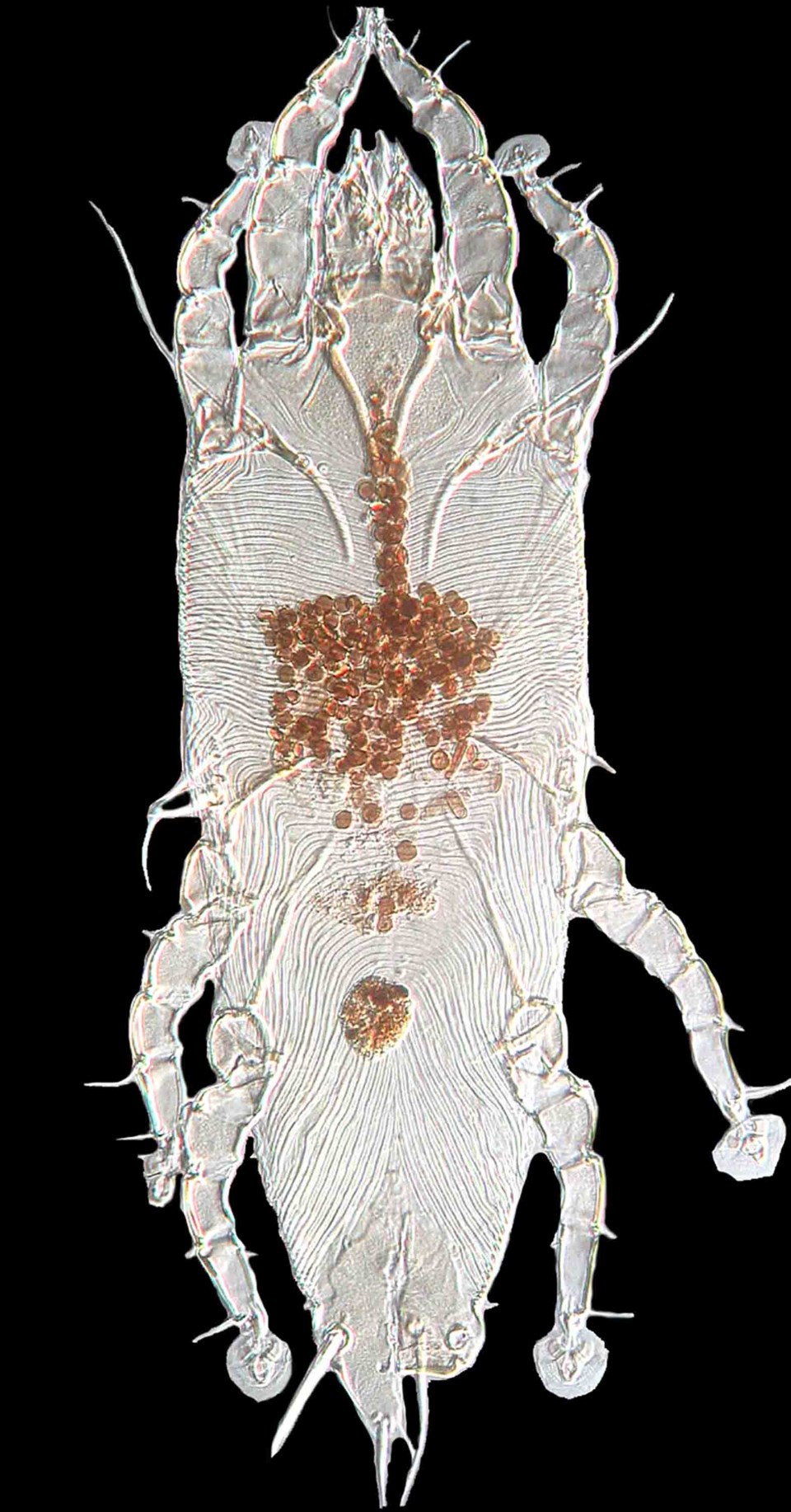

Proctor said she decided to look into the matter in 2017 after collecting thousands of feather mites from around the world over the decades. She teamed up with summer student Arnika Oddy-van Oploo – “who is just amazingly good at doing boring things” – to examine the gut contents of some 1,300 mites from 190 bird species under the microscope. (The mites were treated with lactic acid to make them transparent.) They later partnered with Spain’s Jorge Doña, who was doing a similar but smaller study on mite diets using DNA analysis.

The team found fungi and bacteria made up the vast majority of the mites’ diets, but found no visual or DNA evidence that the mites ate bird blood, feathers or skin.

“The feather mites are not parasites of the birds,” Proctor said, and might actually be beneficial to them – the DNA analysis found at least some of the fungi they ate were known to eat keratin, an ingredient in feathers.

Mites? On my bird?

“Almost every species of bird has feather mites on it,” Proctor said, with the Australian rhea (ostrich-like) and penguins being the few exceptions. Migratory birds and woodpeckers tend to have the most feather mites, while those who overwinter here (like chickadees) tend to have just one or two species.

There are thousands of species of feather mite, many of which live only on specific spots on the feathers of specific species, Proctor said. That means they’re unlikely to spread to you if you handle a bird that has them. (Nest mites are another story; expect bug bites if you mess with a nest.)

“Not all feather mites are harmless,” she added. This study focused on mites found on the feather surface – those that live in the quill are known to eat feathers.

Proctor said the team found a surprisingly wide mix of DNA in the mites' guts, suggesting the mites were simply eating everything they could lick up instead of being picky. In doing so, they may unintentionally keep their host birds healthy by cleaning their feathers.

This raises some interesting conservation questions, she continued. Zoos, farms and pet stores will often treat birds with pesticides to get rid of lice (which other studies have shown do eat feathers and harm bird health), and in doing so may be killing off helpful mites. More studies are needed to determine if removing mites helps or harms bird health.

Margo Pybus, a wildlife disease specialist with Alberta Fish and Wildlife, said she wasn’t surprised by Proctor’s results.

“Mites are pretty ubiquitous,” she said, and birds are essentially mobile habitat for them. She’s more surprised when she finds a mite-free bird than an infested one.

“Obviously, the mites are finding something to eat ... and the birds aren’t negatively affected by it.”

The study can be found at bit.ly/2UmtuMC.