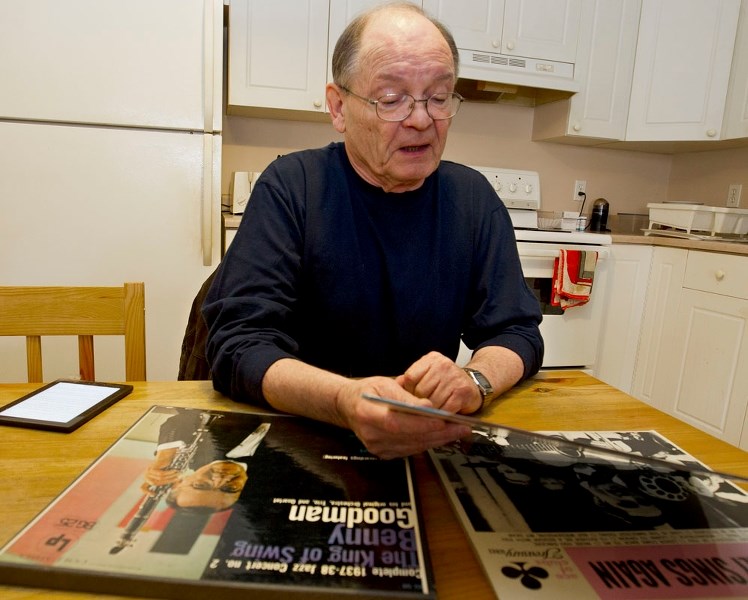

To listen to David Vincent in informal conversation, it quickly becomes apparent that he was born for radio. He has a rich, deep voice, one that speaks with authority but is not imposing.

He is undoubtedly most familiar to Edmonton audiences for being a former host at CHQT radio, where he finished his career after nearly 40 years in the business. But perhaps most of us fans are unaware of the rather auspicious manner in which he entered the world of broadcast radio, as David Sinclair, back in his native Britain.

As a pirate.

"It changed us all," the 72-year-old remarked of his experiences as a young man with pirate radio.

It sounded like he wasn't just talking about himself. Pirate radio actually changed a lot of people. It eventually changed the country too.

"David and his colleagues changed broadcasting history and I think it is vital that their true story is told or people will only remember a glamorized fantasy," added Jon Myer, owner of The Pirate Radio Hall of Fame website (found at www.offshoreradio.co.uk).

Thank the stars that Vincent has finally published his memoirs. Making Waves: Fun and Adventure as a Young DJ on Britain's Offshore Pirate Radio Stations in the mid-'60s is now available as an e-book under his disc jockey name. Heretofore, we were unaware of his seafaring days on various barges and sea forts with Radio Essex, Radio 270 and Radio 390.

Conversation with a renegade

It's not every day that one gets to sit down and have a one-on-one conversation with a red-blooded pirate. I was very much a fan of Vincent's work on CHQT and still remember fondly the days of doing my homework with his voice and his music in the background.

This droll gent bucked the trend half a century ago as a renegade. His youth was fairly austere, he noted, in the stodgy years after the Second World War. The country's leaders were primarily concerned with returning to normalcy, so a lot of the post-war social changes were officially eschewed.

"With the late '50s running into the early '60s, things started to change. The place started to hum; a new generation had risen and had its own wants, which were very different to Mum and Dad who had grown up pre-war."

He became an accounts clerk with a dull suit, desperate for something else. Pretty dry days, he recalled, leading him to feel restless.

"It was the sense that I could end up doing the same thing for years unless I found something I could really get my teeth into. If people want something, they will find it," he said, adding that pirate radio came along at just the right time.

With no experience in radio and, frankly, no experience on the open water, he set out to become a DJ. Unlike television, which allowed for commercial broadcasters, radio in Britain was otherwise restricted solely to the auspices of the British Broadcasting Corporation.

"In 1955, they allowed one commercial television channel as an experiment, but for some reason, they balked at doing the same for radio. All very strange."

According to Vincent, the national radio broadcaster was a bit stuffy for his tastes.

"I am very unkind to the early days of the BBC. When they did stuff, they did it very well. Musically, it was all the 'palm court' orchestra for elderly ladies. If you listened to some of the old BBC 'programmes' of the '50s and '60s, the voices they used were cringeworthy, upper-class accents, which made most of us want to vomit. The poor, strangulated tones coming from these people …"

But the early 1960s were an exciting time for music and BBC Radio just didn't offer the screaming Beatles fans enough airtime for popular tracks.

"Things like music and other entertainments were at the forefront of teenagers' minds. We all wanted what we couldn't get. At that time, it seemed logical to have more than one service, and the only way to get it was to have commercial service. On radio, that's no real problem. It's not expensive like television."

"David and I were part of the post-war baby-boomer generation. There are, and were, a lot of us. That is probably partly why the pirate stations did so well – the DJs were broadcasting to their contemporaries," Myer added.

There were a few colourful and enterprising individuals who took their cues from the Danes, establishing a radio booth and transmitter on vessels just outside of territorial waters, right where national laws would not apply. It was distinct of its time and the mood of its country, he suggested.

That meant that they could play whatever they wanted, and the broadcast would be strong enough to still reach the radio sets back at home.

"The future didn't look exciting until this phenomenon. Somehow I just knew that this was what I wanted to do. I had to rush around trying to find out how to do it."

A naïve letter to Dick Palmer, the owner of Radio Essex, led to Vincent's eventual hire. He still remembers his first day on the job.

"Getting there was an interesting time. I had never been on the water before. You don't if you live near London. I got on board this small fishing vessel. Thank God it was a reasonable day because I didn't get seasick."

"When we got to this rusting structure, you look up at the damn thing and wonder and find that you've got to first jump off the boat and grab a rusty iron ladder, haul yourself up to a landing stage that had half the planks missing and then guys above would lower rope. I nearly cracked, I tell you! Like most blokes, you didn't dare let it be known."

As pirates go, these were probably the most respectable and clean-cut young blokes you've ever met. Vincent averred that propriety was still king even though they were definitely bucking the establishment.

"We were! None of us came from the hippie side of things, which was all the rage in the '60s. We wanted to have a good time but we wanted to do it properly, and make a buck or two. I was never tempted into the stupidities of the time. None of us were drug-takers of any kind, which may seem weird."

Vincent managed to bounce between a few different pirate stations, some on boats and others on various sea forts, abandoned stationary platforms that had been previously installed and used by the UK's armed forces.

"For youngsters, like me at the time, it was also exciting. It was also a hell of a lot of fun."

Myer noted that 250,000 people visited his website last year alone, a testament to the fondness that many still have for pirate radio and its personalities.

"Pirate radio provided the soundtrack to my – and many other people's – teenage years," he said.

That is until the British parliament devised the Marine Offences Act of 1967, shutting the pirates down. Commercial radio was later permitted, leaving Vincent and his fellows to feel like they won the larger moral victory.

He said that he wouldn't have done things any other way.

"I couldn't imagine doing anything else."

Although, he added, he did have one regret.

"The only regret I have is that we didn't have ammunition for the guns [to ward off the government]. Symbolically, of course," he laughed with that trademark throaty laugh.

Review

Making Waves: Fun and Adventure as a Young DJ on Britain's Offshore Pirate Radio Stations e-book by David Sinclair

135 pages

$10.32 on Lulu.com (also iTunes and Amazon)