At 81, Jerry Bayrak knows the importance of telling stories. They keep the past alive, and that's the key.

“My great-grandmother was there. My grandmother and grandfather, my uncle and my mom was born in the camp,” he said, referring to the Spirit Lake internment camp near Amos, Quebec.

The Spirit Lake was one of 24 internment camps established between 1914 and 1920 during Canada’s first internment operations. It was the second largest camp in the country with 1,200 men, women, and children – the majority of which were Ukrainian – unjustly interned as enemy aliens. Spirit Lake was one of only two camps where families were interned together. Other camps contained only unmarried men.

“They said that it was all voluntary but if you see any of the photographs, there were soldiers with fixed bayonets on their rifles. Apparently one man was shot trying to escape from Spirit Lake. Amos at the time had 500 citizens. I think there was 1,500 in the camp itself and it was in a muskeg swampy area. The men ... every day they had chores. They cleared 600 acres of muskeg and trees.”

He agreed it must have been backbreaking work in harsh conditions with little to no concern for their well-being.

“Imagine going into winter for a 12-hour day and you get sweaty or wet and come back trying to dry your clothes for the next day. Or in the summer: mosquitoes, black flies, sweating. You didn't have a shower. You didn't come home and throw it into the laundry. I would imagine it was pretty tough. From what mom said talking to my grandfather, if you didn't work, you didn't get food.”

His great-grandmother died of tuberculosis, as did his grandmother, who was only 32. Years after her internment, his mother also ended up in hospital for TB. His sister was only in Grade 10 when she ended up in hospital. Tuberculosis again. Four generations of his family suffered for no reason other than they came from Ukraine.

His mother died in 2008. That was about the same time Bayrak started to tell their stories to a wider audience. He had reached his limit of people not even knowing the injustices against his family and so many others. The history of the internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War is much more common knowledge but is entirely different because of how the two groups were treated, he said.

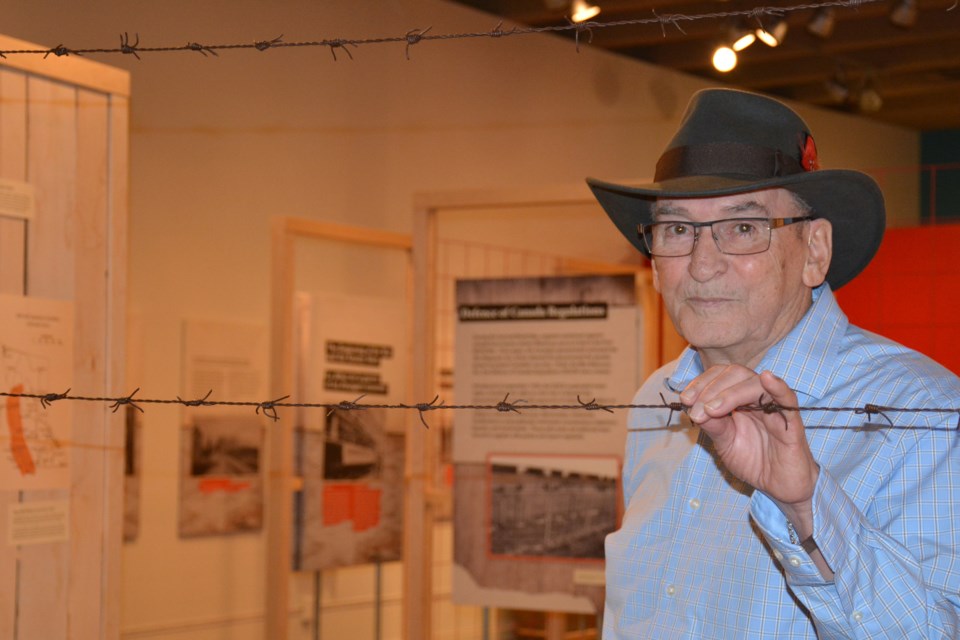

“The Ukrainians ... they took everything, sold machinery, equipment, land at 10 cents on the dollar. When the Ukrainian Canadians left, they didn't get anything with them. I think the Japanese, over years, I think they got well over $50 million. Each citizen was given something. The Ukrainians were given nothing. ‘Don’t let the barbed wire catch you on the way out.’”

During the First World War, approximately 88,000 people were forced to register as “enemy aliens,” including more than 8,500 mostly Ukrainian and German immigrant men who were wrongfully imprisoned in internment camps across Canada.

Bayrak is featured in a documentary film on the Ukrainian Canadian internment that will be screened at the Musée Héritage Museum on Saturday. That Never Happened tells the story of Canada’s first national internment operations between 1914 and 1920. It’s another way of bringing people’s attention to our country’s history, something that is elaborated on to a much greater extent in the museum’s current exhibit, Enemy Aliens, which came from the Canadian War Museum.

Museum curator Joanne White wanted to use the film as a way of expanding the public’s understanding so Ukrainian Canadian internment will become common knowledge too.

“We've had a lot of people come in that didn't know about it, including Ukrainian families from Alberta,” she began. “It wasn't something that was talked about a great deal. Our goal has been to just get the word out, educate people and by showing the film we’re able to make that a more concrete and better understood piece of history.”

The event is free and takes place at the museum starting at 2 p.m. on Saturday, Jan. 11.