John Kennedy never saw combat in his 20 years with the Canadian Armed Forces. He never had to shoot anybody; never witnessed buddies getting blown up.

But the peacetime veteran's horrific experience in Rwanda after the civil war that saw the slaughter of 800,000 Rwandans still haunts his dreams and troubles his waking hours.

Kennedy was sent to the African country in 1994 right after the genocide. He spent four months attached to a Field Ambulance as the sergeant in charge of construction troops restoring power and water services to communities there.

"That's where my PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) came from--the atrocities I saw in Rwanda," he said. "Kids with missing hands, missing feet.

"There were bodies on the beaches, bodies floating in Lake Kivu. We had to clear a septic system in a church that was gutted and where the bodies of nuns and the priest and bishop had been dumped. When the rainy season hit, the church flooded and we found those bodies in the sump stuff. That's one of the nightmares that I have."

Kennedy said one thing gave him solace. Doctors asked him to build an incubator during his first month there, after 30 babies died of hypothermia due to malnutrition. Kennedy and his soldiers used parts scavenged from a dairy to build the incubator, saving the first two babies put into it. The babies hadn't been expected to last the day, but they survived.

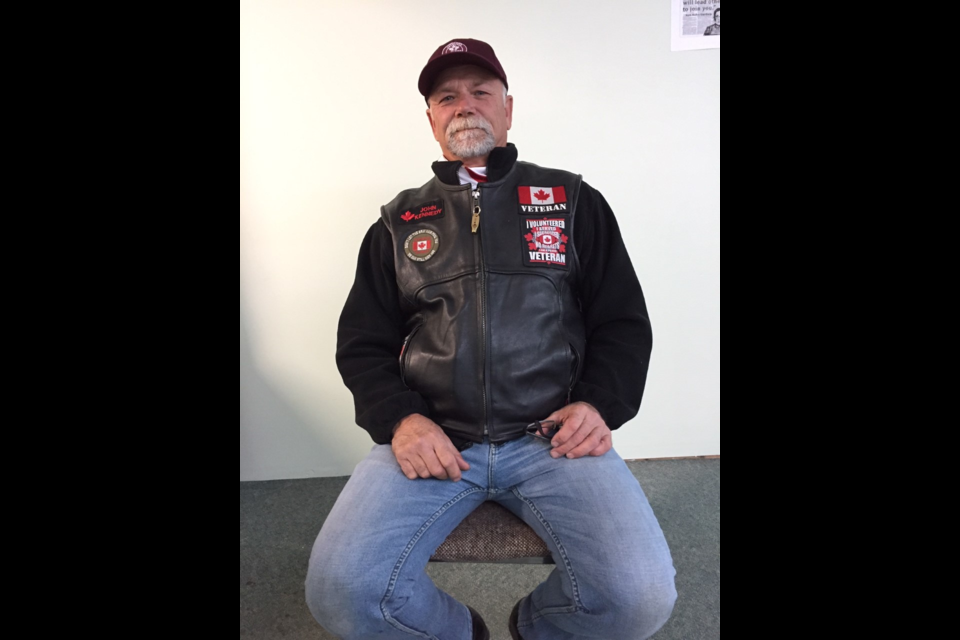

Kennedy, now 61, retired as a sergeant in 1997. But like many soldiers who were deployed, he wasn't the same person when he came back.

"After Rwanda I was so hard on my kids because of the poverty I'd seen. My kids wanted a new Game Boy and these kids were playing on the ground with a corn cob pretending it was a truck, then wiping it off and eating it. They were washing and drinking water that cattle were using to do what cattle do. It changed me mentally from our North American expectations of life."

Kennedy also suffered depression, anxiety, anger, suicidal thoughts, hallucinations and nightmares. But he didn't realize he had changed. "I was 'there's nothing wrong with me, what's your problem?'

"It took me until 2011 to reach out for help because I didn't want to," he said. "The military takes a civilian, breaks them down and builds them back up into a soldier. But when someone gets out of the military there is no transition back. We're dumped into a civilian life we can't understand anymore."

Kennedy went to the Operational Stress Injury Clinic in Edmonton, which offers mental health services to veterans and Canadian Forces and RCMP members and their families. He started talk therapy but said it didn't help.

"I thought I was absolutely going crazy, which brought up the suicidal thoughts that I'm not normal, I can't function.

"Two years ago, Kennedy connected with a Saskatchewan veteran on social media who told him about the long term side effects of Mefloquine, an anti-malarial drug issued by the military to soldiers stationed in Somalia, Rwanda and Afghanistan.

Suddenly, he found an explanation for his anxieties, anger and suicidal thoughts. A subsequent brain mapping found that Kennedy had a chemical brain injury.

"When I got that report, it was such a relief. It wasn't a solution, but the confirmation was overwhelming. I sat out in the parking lot and cried for an hour because I had thought I was crazy," Kennedy said, tearing up at the memory.

Kennedy is among a growing number of former soldiers suing the Canadian government over Mefloquine. The soldiers say they were never told of the warnings about Mefloquine's long term side effects. Mefloquine is still used by the military, but as of 2016 is no longer its front line malarial drug.

Kennedy still has depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts, but new treatment has helped. He also has short term memory loss which makes it difficult to remember what he's reading. His cognitive abilities aren't great, he said, and he suffers from tinitis and neuropathy which causes numbness and tingling.

Today, Kennedy spends much of his time volunteering with the Veterans Association Food Bank which opened in Edmonton this month.

"I've got 11 grandchildren and that's one of the things that keep me alive."

Around Remembrance Day, Kennedy asked if he thinks the public remembers veterans.

"It has a lot of meaning to me and all veterans because we experienced it. The general population does not appreciate what a soldier actually sacrifices," he said. "It doesn't mean you or somebody beside you has to die."

Still, Kennedy said he has no regrets about his time in the military serving his country and what it cost him mentally and physically.

"The military changed me from a boy into a man. It taught me responsibility and leadership. I learned a trade. I made many, many acquaintances."

As an embroidered patch on his jacket declares: 'I Volunteered, I Served, I Sacrificed, No Regrets, I am a Proud VETERAN.'

Help for Veterans

The Veterans Association Food Bank (veteransassociationfoodbank.ca), run by veterans for veterans, provides basic needs and a stable environment for veterans affected by loneliness, addiction and mental health.

Edmonton vets can also connect with mental and physical health supports, financial, housing, crisis and community services through the Edmonton Veterans Service Centre 1 888 228-3871; [email protected].